A Ghost Town Worth Visiting

In its heyday, Brownsville, Pennsylvania supported three large national banks that issued a combined $5 million in notes, a couple of which the author has in his collection.

By Mark Hotz

For quite some time, I have wanted to visit Brownsville, Pa., located about 40 miles south of Pittsburgh along the Monongahela River. I had been told about this place and had seen a few photos. At one time, Brownsville had been a teeming place, with a population of 10,000 and three huge national banks. But the region had fallen on hard times and the downtown area reduced to ghost town status.

I had the opportunity to fulfill this bucket list item this past September, when I traveled to Monroeville, Pa., for a convention of Military and Royal Orders and Decorations, another area of collecting interest for me. I was able to be in and out in a few hours, having purchased some lovely items brought especially for me from Canada. I had the time to go to Brownsville and was determined to do so. I was not disappointed with what I found.

First, some history. Entrepreneur Thomas Brown acquired the western lands in what became Fayette County, Pa., around the end of the American Revolution. He realized the opening of the pass through the Cumberland Narrows, and war’s end, made the land at the western tip of Fayette County a natural springboard for settlers traveling to points west, such as Kentucky, Tennessee and Ohio. Many travelers used the Ohio River and its tributary, the Monongahela. Eventually, the settlement became known as “Brownsville” after him.

In the 1780s, Jacob Bowman bought the land on which he built Nemacolin Castle; he had a trading post and provided services and supplies to emigrant settlers. Brownsville was positioned at the western end of the primitive road network (Braddock’s Road to Burd’s Road via the Cumberland Narrows pass) that eventually became chartered as the Cumberland toll road and later, after the Federal Government appropriated funds for its first-ever road project, known as the National Pike. Well after tolls were removed, it became the present-day U.S. Route 40, one of the original federal highways.

Brownsville developed as an early center of the steamboat-building industry in the 19th century. The Monongahela converges with the Ohio River at Pittsburgh and allowed for quick traveling to the western frontier. From 1811 to 1888, boatyards produced more than 3,000 steamboats. Steamboats were gradually supplanted in the passenger-carrying trade after the American Civil War as the construction of railroad networks surged but concurrently grew important locally on the Ohio River and tributaries as tugs delivering barge loads of minerals to the burgeoning steel industries growing up along the watershed from the 1850s. Steamboat propulsion would not be replaced by diesel-powered commercial tugs until the technology matured in the mid 20th century. The first all-cast iron arch bridge constructed in the United States was built in Brownsville to carry the National Pike (at the time a wagon road) across Dunlap’s Creek. The bridge is still in use in 2018.

Yet the rise of the steel industry in the Pittsburgh area led Brownsville to develop as a railroad yard and coking center, generally integrated into other towns within the valley, so Brownsville and West Brownsville were tied to regional operations, and while no one yard had space enough to be large, each township along the river shared resources and functioned as an elongated yard system. With its new role as Railroad center and coking center together with the decline of outfitting, the town gradually lost its diverse mix of businesses but nonetheless generally prospered during the early 20th century through the 1960s. Brownsville tightened its belt during the Great Depression, but the local economy resumed growth with the increased demand for steel during and after World War II, when many infrastructure projects hatched the improved and rerouted U.S. Route 40 over the new high level bridge, clearing up a perennial traffic congestion problem.

In 1940, 8,015 people lived in Brownsville. In the mid-1970s, after the OPEC Oil Embargo of 1973–74 triggered a recession with the restructuring of the steel industry and loss of industrial jobs, Brownsville suffered a severe decline, along with much of the Rust Belt. Generally, the region has declined in population and vitality ever since. By 2010, the population was 2,331, as younger people had moved away to areas with more jobs.

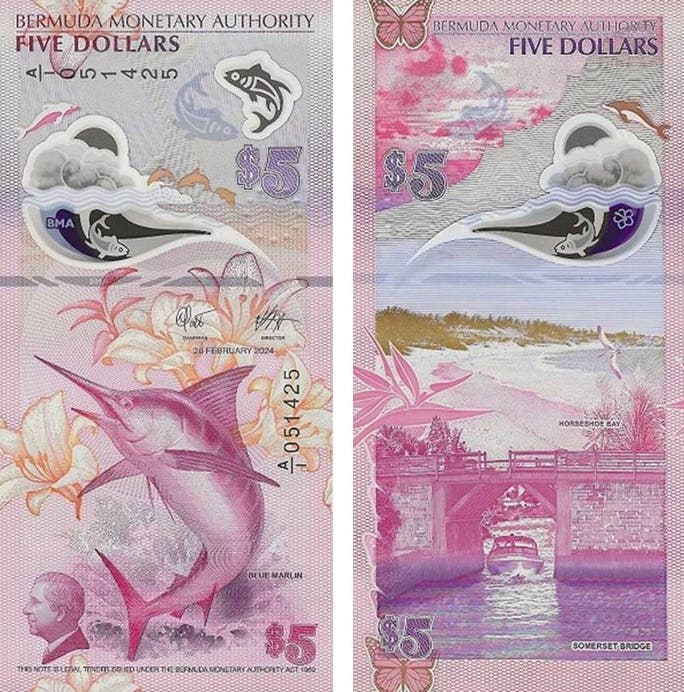

The downtown area is Market Street, which is reached off of US 40, which snakes around the town. During its heyday, it supported three large national banks. These were the Second National Bank, charter #2673, which succeeded the First National Bank when it was liquidated in 1882; the Monongahela National Bank, charter #648, which was chartered in 1864 and closed by the receiver in 1931; and the National Deposit Bank, charter #2457, chartered in 1880. These were all very large banks, with the two former issuing over $2,000,000 each in circulation, and the latter with $1.3 million. Though just one note is known from the First National Bank, large and small notes are known from the large three, though not as readily seen on the marketplace. The popularity of these banks, due to the ghostly nature of Brownsville, keeps them mostly the large notes in tight hands.

Entering Brownsville on Market Street from US 40 is quite the experience. One is immediately amazed by the number of large and abandoned buildings lining both sides of the street. In the center of the downtown area is a large parking area where other large buildings once stood. I parked my car and wandered around the abandoned street. The Flatiron Building at the head of Market Street is owned by the Brownsville Area Revitalization Corporation (BARC) and was open. It has a lot of information about the town and many relics on display. It sits directly across Market Street from the abandoned Second National Bank building, which is part of a string of abandoned buildings culminating in the columned Monongahela National Bank building, also abandoned, which sits next to the parking lot.

Just behind the Flatiron Building and across from the Second National Bank is Brownsville’s huge and once very proud Union Station, a seven-story red brick structure reminiscent of some of the finest railroad stations in the country. Behind the station and along the river run the railroad tracks that once brought business and customers to Brownsville from Pittsburgh. The station is abandoned and the tracks derelict. A couple rusty parking meters sat in front of the station, and I wondered how long it had been since anyone had paid for parking in the abandoned downtown.

Walking south along Market Street, I saw many abandoned and boarded up stores leading uphill to the National Deposit Bank building, which sat atop a hill at the other edge of downtown. The only operating businesses were a pharmacy (a project supported by BARC) and a diner named the Fiddler. It was something to gaze back on the entire row of abandoned blocks from in front of the National Deposit Bank (also abandoned).

I have included a series of photos I took of various parts of downtown Brownsville. It is one of the best ghost downtowns I have seen anywhere, mainly due to the plethora of large buildings. I also included a photo of the huge vault inside the ruined main floor of the Monongahela National Bank.

I was able to add two very nice large notes from two of Brownsville’s banks to my collection; I have included photos of these and a large note from the National Deposit Bank. All of these banks issued small notes as well.

Although Brownsville is off the beaten path, it is well worth the visit. There are many small old coal and steel towns nearby that are also worth visiting, though Brownsville is the queen of the Monongahela ghosts.

Readers may address questions or comments about this article or national bank notes in general to Mark Hotz directly by email at markbhotz@aol.com.

This article was originally printed in Bank Note Reporter. >> Subscribe today.

If you like what you've read here, check out Standard Catalog of United States Paper Money.