Bank notes forever tied to Wild Bunch

Pinkertons used serial numbers to track rail heist loot Just before the bank’s closing on Monday, Oct. 14, 1901, a well-dressed woman walked into The Fourth National Bank of Nashville,…

Pinkertons used serial numbers to track rail heist loot

Just before the bank’s closing on Monday, Oct. 14, 1901, a well-dressed woman walked into The Fourth National Bank of Nashville, Tenn., where she hoped to exchange some crisp new bills for less troublesome currency. She placed a bundle of $10s on the marble counter and asked bank teller McHenry for $50s or $100s in exchange. All may have gone well for this would-be passer of stolen bank notes had McHenry not become suspicious, but he did, and after consulting a circular detailing the serial numbers of missing notes, he summoned the local police.

Circulars, like the one McHenry found so useful, had been showing up across the country, sent by Pinkerton’s National Detective Agency, and provided the identifying numbers for uncut sheets of National Bank Notes stolen a few months prior in a brazen Montana train robbery by Harvey “Kid Curry” Logan, Ben “The Tall Texan” Kilpatrick, Orlando Camillo “Deaf” Hanks and, it was believed at the time, Robert LeRoy Parker (Butch Cassidy) and Harry Longabaugh (the Sundance Kid).

Receiving McHenry’s call, Lt. Marshall and city detectives Dwyer and Dickens hurried to the bank, where they placed the woman, who gave her name variously as Annie Rogers or Maud Williams, under arrest. Rogers (Williams) was described as “good looking, of slight build, and a heavy head of dark brown hair. She is of dark complexion and high cheek bones, with piercing black eyes.”[1]

Her eyes were said to “fairly dance as she speaks,” related a story in the Oct. 22, 1901 Jackson (Mich.) Citizen datelined to Nashville, Oct. 18. But this didn’t help her with the law. Finding $550 in suspect bills on her, Rogers (Williams) was accused of attempting to pass forged bank notes.

Annie told the detectives that she had just arrived in the city and had been given the notes by a man she had been with for only two weeks. But Annie was no neophyte in dealing with criminals, nor was she the only one circulating some of the $40,000 in large-size $10s and $20s looted from a shipment to The National Bank of Montana, Helena, Mont.

Annie was the girlfriend of train robber, murderer Harvey “Kid Curry” Logan. Logan was a member of the notorious Wild Bunch, who were known to employ northern Wyoming’s Hole-in-the-Wall as one of their hiding places and were suspected of and involved in several bank and train robberies leading up to this one.

Boldest robbery ever

The stolen notes were from an assault by Kid Curry and others on Great Northern Transcontinental’s express train No. 3 near Wagner, Mont. on July 3, 1901, as the nation and the train’s passengers anticipated the Fourth of July.

“The robbery was one of the boldest that ever occurred in the West,” the July 5, 1901 issue of the Boston Herald related in a piece datelined Havre, Mont., July 4, 1901. “As [the train] was leaving Malta yesterday afternoon Conductor Smith noticed what he supposed to be a tramp on the front end of the mail car, next to the engine. He tried to drive him off after the train started, but the man pulled a revolver, and Smith returned to the coaches, and, as Sheriff Griffith of Valley county was on the train, arranged with him to arrest the man at the next siding.”

“When the train approached Exeter…, the conductor signalled the engineer to stop, but the train only slackened speed. The conductor signalled a second time, but the train did not stop. Engineer Jones was during this time covered by a gun, and was told by the tramp that, if the train stopped, he would kill him.

“Three miles east of Wagner the engineer was forced to stop the train, and two more men appeared, armed with Winchesters. The robbers commenced firing, and the passengers thought children were celebrating the Fourth. Brakeman Whiteside stepped from the rear end of the train and was shot through the right arm. Mr. Douglas swung out on the steps and was shot through the left arm. Miss Smith put her head out of a window and a bullet ploughed into her arm.”

Dynamite, which “both confederates that appeared in the ravine were liberally supplied” with, was used to gain access to the express car. “The express men were compelled to leave the car at the point of a rifle and the through safe was immediately dynamited.” The first charge not succeeding, four more blasts were necessary. “The robbers hurriedly gathered in its contents, consisting of specie shipments, drafts, coin and valuable negotiable paper, and retreated, keeping the train crew and passengers off at the point of their rifles.”

“All three disappeared in the ravine and were seen later, one mounted on a bay horse, one upon a white horse, one upon a buckskin, heading southward at a furious gait, the booty being plainly visible in a sack thrown across the saddle bows of the rider upon the buckskin horse…,” explained the July 5, 1901 issue of the Charlotte (N.C.) Observer. “The gang headed for the Little Rock range, lying across the Milk river, in an almost inaccessible country, consisting mainly of bad lands. Posses were immediately organized in pursuit…”

Butch and Sundance suspected

As the men were masked and details of their appearance were at best sketchy, authorities considered many known outlaws. By a month after the robbery, the suspects named by Pinkerton’s National Detective Agency included Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.

The Aug. 14, 1901 issue of the Anaconda (Mont.) Standard reported:

“The sheriff’s office is in receipt of a copy of a circular with which the country has been flooded by the Pinkerton National Detective agency relative to the Great Northern train robbery on July 3 last, and the four men who are suspected of the crime,” adding that “after a thorough investigation the detectives have come to the conclusion that the robbery was probably committed by Harvey Logan, alias Harvey Curry, alias Kid Curry, alias Bob Jones, alias Tom Jones; George Parker alias ‘Butch’ Cassidy, alias George Cassidy, alias Ingerfield; Harry Longabaugh [Sundance], alias Harry Alonzo; O.C. Hanks, alias Camilla Hanks, alias Charley Jones, alias Deaf Charley.”

Descriptions were as follows:

“Logan – Fugitive from justice; murdered Pike Landusky, Dec. 25, 1894; committed a number of robberies since, including the Union Pacific train robbery at Wilcox, Wyo., June 2, 1899; murder of Sheriff Hazen, one of the pursuers.

“Parker – Criminal principally in Wyoming, Utah, Idaho, Colorado and Nevada; served several terms in the Wyoming petitentiary [sic] for grand larceny, and was pardoned Jan. 19, 1896.

“Longabaugh – Served 18 months in jail at Sundance, Wyo., for horse stealing when he was a boy; December, 1892, with Bill Madden and Harry Bass, held up the Great Northern train at Malta; Bass and Madden arrested and convicted, sentenced to 10 and 14 years respectively; Longabaugh escaped and has been a fugitive ever since; on June 28, 1897, under the name of Frank Jones, participated with Harvey Logan (Kid Curry), Tom Day and Walter Putney in the Belle Fourche, S.D., bank robbery; all were arrested, but Logan and Longabaugh escaped from the Deadwood jail Oct. 31, 1897.

“Hanks – Wanted for murder at Las Vegas, N.M.; arrested in Teton county, Mont., in 1892, and sent to the penitentiary for 10 years for holding up the Northern Pacific train at Big Timber; released from penitentiary April 30, 1901.”

In Tiger of the Wild Bunch: The Life and Death of Harvey ‘Kid Curry’ Logan, author Gary A. Wilson identifies fresh-out-of-jail Orlando Camillo “Deaf” Hanks as the “tramp” spotted having boarded the Great Northern express train between the coal tender and the blind baggage car.

“Conductor Alexis Smith spotted him and asked for the fare,” Wilson wrote. “Instead, he got a revolver in face and an order not to stop the train. Hanks crawled over the coal tender into the engine cab. He directed engineer Tom Jones and fireman Mike O’Neil to stop the train at the eastern edge of the Exeter Creek bridge.”[2]

That was when the other two outlaws appeared from under the bridge. According to Wilson, they were Ben “The Tall Texan” Kilpatrick and Harvey “Kid Curry” Logan. A fourth outlaw stayed with the horses but is unidentified, though one theory was that it was Laura Bullion, Kilpatrick’s girlfriend, disguised as a man.

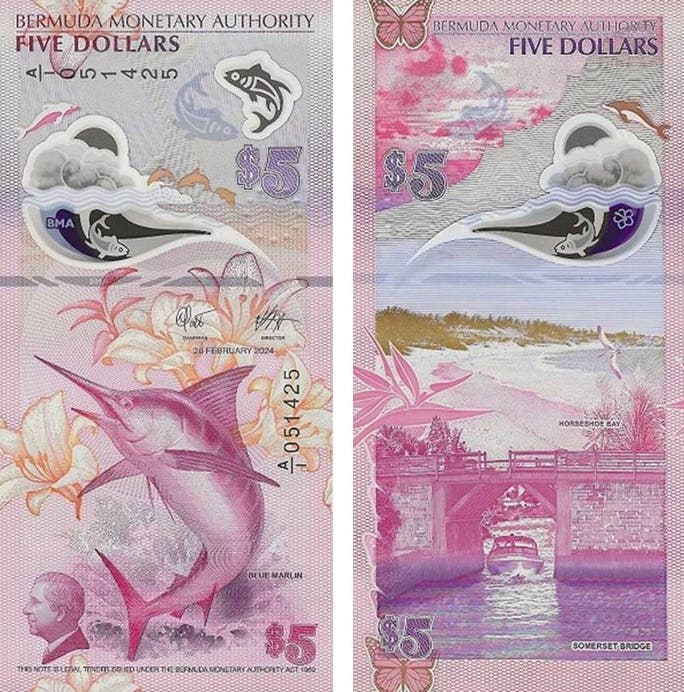

$40,000 in Brown Backs

Although early accounts placed the amount stolen at $83,000, this figure was basically halved, with $40,000 said to have been taken in the form of uncut sheets of large-size National Bank Notes being shipped by the Treasury to The National Bank of Montana, charter 5671, in Helena, Mont. Another $500 was described in one account as “Great Northern money” that was in a through safe.

The Pinkertons supplied serial numbers for the notes, which included $24,000 in $10s and $16,000 in $20s. The July 6, 1901 issue of the Washington, D.C. Evening Star, related:

“‘In speaking of the Great Northern train robbery at Wagner, Mont., last Monday, their information was that the $40,000 incomplete national bank notes which were shipped on June 28 to the National Bank of Montana of Helena were among the funds secured by the robbers. It appears that there were 800 sheets of these unsigned notes, of four notes to a sheet, three $10’s and one $20. The bank numbers run serially from 1201 to 2,000, but inclusive, and the treasury numbers were from Y934,349 to Y935,148. The bank numbers were printed in the lower left-hand corners of the notes and the treasury numbers in the upper right-hand corner. The charter number was 5761 [sic , 5671] printed in bold face brown figures across the face of each note. It is stated at the department that as soon as notes of this character are shipped to the bank they are regarded by law as in circulation and are redeemable by the government as well as the bank that has on deposit at the treasury sufficient bonds to cover their redemptions. As the express companies are under bond for the safe delivery of all shipments of this character, they alone are responsible, so that the government and the bank are fully protected from loss.”

National Bank of Montana, Helena

The National Bank of Montana was organized only a few months prior to the robbery, with Thomas A. Marlow, president; Albert L. Smith, vice president; and T.C. Kurtz, cashier. It was situated in the same building in Helena formerly occupied by the Montana National Bank. Of the new bank’s establishment, the Jan. 10, 1901 issue of the Butte (Mont.) Weekly Miner wrote, under the title “New Name, But The Same Bank”:

“Helena, Jan. 9. – The Montana National bank, one of the best known financial houses in Montana, will tomorrow cease to exist, the corporation having turned over its business to a new bank which will be called the National Bank of Montana.... The new bank will have practically the same management as the old. The change to be made tomorrow was found to be desirable as a large part of the capital stock of the old bank formed parts of estates not yet settled. The bank was organized by the late Charles A. Broadwater, whose estate owned a large block of its stock. The new bank will open with a capital stock of $250,000 and surplus of $62,000—the same capital the old bank had. T.H. Marlow, formerly president of the Montana National, will be president of the new, with A.L. Smith, vice president and Thomas C. Kurtz, cashier. Among the stockholders of the new bank are J.H.J. Hill, president of the Great Northern; Jas. H. Eckels, formerly comptroller of the treasury; Joseph Rosenbaum and A.G. Becker of Chicago and Henry Bratnober of San Francisco.”

Ironically, J.H.J. Hill was the owner of the railroad the Wild Bunch hit. Wilson writes, in relation to the robbery of the Great Northern, that Kid Curry told express messenger C.H. Smith during the robbery, “We ain’t going to hurt anybody, we just want Jim Hill’s… money.”[3]

Curry also had ties to National Bank of Helena president Marlow, at least according to an article in the Jan. 16, 1902 issue of the Grand Forks (N.D.) Daily Herald. It explained that:

“T.A. Marlow, president of the National Bank of Helena, today identified the picture of Harvey Logan, the man who was recently arrested at Knoxville, Tenn., with Bank of Montana notes in his possession as that, of ‘Kid’ Curry.… Mr. Marlow formerly employed Curry as a cowboy and knew him well.”

According to the Standard Catalog of National Bank Notes, by Dean Oakes and John Hickman, The National Bank of Montana, Helena, Mont., chartered on Jan. 8, 1901, issued Series of 1882 Brown Backs in 10-10-10-20 sheets with bank serials 1-10200; 30,600 in $10s and 10,200 in $20s.[4]

The bank, which also issued notes of later types, was consolidated with the American National Bank of Helena, charter 4396, on May 23, 1931. The amount of large outstanding at close was $22,640.

According to the Nov. 8, 1901 issue of the San Francisco Call, the heist also included $500 (perhaps the $500 described in other publications as “Great Northern Money”) in new bank notes on the American National Bank of Helena “to the extent of $500, $300 of which was in $10 bills and $200 of which was in $20 bills – Serial number 3423 to 3432 inclusive; Government number V662,761 to V662,770 inclusive; charter number 4396.

“These incomplete bank notes lacked the signatures of the presidents and cashiers of the banks named, and may be circulated without the signatures or with forged signatures.”

“The robbers also stole 360 money order blanks of the Great Northern Express Company, upon which payment should be refused if presented. The numbers of these are as follows:

“Series B – 795,000 to 795,049 inclusive, 795,150 to 795,249 inclusive, 795,300 to 795,319 inclusive, 866,700 to 866,719 inclusive, 866,740 to 866,759 inclusive, 866,800 to 866,839 inclusive, 867,000 to 867,019 inclusive, 867,060 to 867,119 inclusive.”

The American National Bank of Helena was chartered in 1890. With its absorption of The National Bank of Montana in 1931, along with The Montana Trust and Savings Bank in Helena, it became the First National Bank and Trust Company of Helena, charter 4396.5 The president of the American National Bank at the time of the robbery was Thomas C. Porter and the cashier was V.J. Gould.[6]

During the period in question, the American National Bank issued 10-10-10-20 sheets of Series of 1882 Brown Backs bearing bank serials 1-9000, with 27,000 $10s and 9,000 $20s.[7]

Notes spotted

It wasn’t long after the robbery that more of the loot, such as the notes Annie Rogers’ tried to pass in Nashville, began showing up.

The Oct. 13, 1901 issue of the Anaconda (Mont.) Standard reported under the headline, “Helena Bank Note Passed in St. Louis,” from a St. Louis dispatch datelined Oct. 12 that: “Joseph Wilson, a clerk in charge of the wholesale stamp department at the St. Louis postoffice, received through his window this morning a $10 treasury note, purporting to be issued by the national bank of Helena, Mont., but containing signatures which are not those of the president and cashier of the bank.”

The note, which the Standard said was believed to have been from the Great Northern robbery, carried the names of Thomas B. Hill, president, and John R. Smith, cashier. It further observed that T.A. Marlow was president and A.L. Smith was the cashier.

Smith was, in fact, the vice president. The cashier at the opening of the bank under the new title was T.C. Kurtz.[8]

“Good Work for Cashier Bynum” reads another report of the missing notes, from the Oct. 12, 1901 issue of the Weekly Advocate, Baton Rouge, La. The newspaper explained to its readers that no one really pays attention to the signatures on National Bank Notes and “they could not even know who were the officers of the hundreds of National banks and could neither detect a forgery nor tell if the right names were signed,” it was therefore amazing what cashier Bynum of the Louisiana State Bank had done.

“Yesterday morning one of these bills [a $10] fell into the hands of Mr. Wade R. Bynum of the Louisiana State Bank,” the Weekly Advocate recorded. “Though only a few months in the banking business, his eye at once told him that it was one of the stolen bills.

“The president of the Helena bank is T.A. Marlow and cashier, Thos. C. Kurtz.

“The bill presented was signed by Chas. Smith, cashier, and W.D. Hill, president. These were of course fictitious names. The charter number of the bill was 5671, government number ‘Y’ 934817. These numbers correspond with one of the stolen bills.

“It is almost certain that a number of these bills are being circulated here and parties ought to be careful in taking new bills.... Mr. Bynum is to be complimented upon his expert work and the promptness with which he ascertained the false bill.”

The New Orleans Clearing House sent out a warning about the stolen money, as reported in the Oct. 10, 1901 issue of the New Orleans Times-Picayune. Under the heading, “Montana Money,” the Times-Picayune wrote:

“The warning sent out by the New Orleans Clearing-house Tuesday to every bank and financial firm in this city relative to the discovery of a number of incomplete bank bills that have been surreptitiously placed in circulation caused a closer scrutiny of $10[s] and $20[s] passing current than was ever before known in New Orleans.”

The Times-Picayune added that it was strange that none of the stolen paper money had yet made it to the subtreasury there.

“Mr. C.J. Bell, the United States subtreasurer, has been on the lookout for those bills for several weeks, as he was minutely informed at the time relative to the amount that was stolen and the exact description of the bills through circulars sent out by the United States treasury department at Washington, and distributed through the United States.

“It was only with the past few days that one or two of those incomplete bills turned up.

“Captain Patrick Looby, United States secret service agent, has been quietly and patiently at work ever since the circulars descriptive of the bills and of the robbers (with the latters’ photographs) were received by him from the department at Washington.”

Looby, the newspaper said, had been making the rounds of local banks over the past couple of days looking for any suspicious notes and, at one of the banks, had found a $20 that he requested the cashier file away “for the purpose of using it as evidence should further developments ensue.”

“Captain Looby is of the opinion that the robbers have been laying their plans for some time, with carefulness and deliberation, to float those bills as far as possible from the scene of the hold-up and from the city in which the banks are doing business,” the Times-Picayune story continued. “It is probable that they will go slow now, or even stop altogether, because of the discovery and publicity by bank officials and the newspapers.”

Suspects ‘sweated’

More of the money appeared in St. Louis in November 1901. The Nov. 7, 1901 issue of the San Francisco Call reported under a St. Louis dateline of Nov. 6 that:

“The police have in custody at the Four Courts a man and a woman suspected of complicity in the robbery of an express car on the Great Northern Railroad near Wagner, Mont. July 30 [sic , 3] last, when the safe was blown open with dynamite and a consignment of unsigned notes for the National Bank of Helena, Mont., amounting to between $50,000 and $100,000 was stolen. Of this amount $8500 in new notes of the Helena bank were recovered, having been found in the possession of the man and woman, who were registered at the Laciede Hotel as Mr. and Mrs. J.W. Rose. They arrived at the hotel last Friday and announced that their stay in the city would probably last several weeks.

“Last night the man was taken into custody and to-day the woman was arrested just as she was about to leave the city. Their arrests followed the passage of several notes of the Helena National Bank that were supposed to have been stolen and the signatures forged. Both prisoners were taken before Chief Desmond to-day and ‘sweated.’

“A photograph of the man was taken and measurements made according to the Bertillon system. Through these and circulars giving a description of the robbers the police identified Rose as Harry Loughbaugh [sic], alias ‘Kid’ Loughbaugh, alias Harry Alonzo.

“Lillian Rose is the a name given by the woman. Both prisoners were examined, but very little was learned from either. Late this afternoon Loughbaugh admitted to Chief Desmond, under the sweating process, that all of the money, $8500, taken from him and Lillian Rose belonged to him, but he would not say where he obtained it. This money has been identified from description as part of the loot of the Great Northern train robbery in Montana July 30 last.”

The Anaconda Standard of Nov. 7, 1901 also incorrectly reported that it was the Sundance Kid who was in St. Louis with Lillie Rose, but at least it got the spelling of his last name right.

In a piece datelined to St. Louis, Nov. 6, it wrote: “Following the arrest last midnight of Harvey Logan alias Harry Longabaugh, alias Harry Alonzo, charged with complicity in the Great Northern Express robbery near Wagner, Mont., on July 3 last, Lillie Rose was arrested in the waiting room of the Laciede hotel this morning. In two grips in her room were found $8,500 in currency of the Helena National bank, known to be a part of the proceeds of the robbery. The couple had been at the Laciede for a week, registered as Mr. and Mrs. J.W. Rose. The woman is about 22 years of age, five feet, five inches high, weighing about 120 pounds, black hair, brown eyes, with long lashes, snub nose, average sized mouth, sallow complexion, dressed in cheap tailor-made dress of tan, white fedora hat, two cheap jeweled hatpins, black shoes, small opal ring on left hand.

“When she was taken before Chief of Detectives Desmond she at first denied that her name was Rose, giving her name as Young, Granger, etc. She at first said that she was from Kentucky, where a stranger, a man whose name she declined to give, had presented her with the money found in her grips, but subsequently she stated that she was from Knickerbocker, Tex., and had met Logan, or Longabaugh, first in Hot Springs, Ark., a few weeks ago. Chief Desmond presented to her attention several watches which had been taken from her valise. [According to Wilson, in Tiger of the Wild Bunch, the loot included eight gold watches that were being shipped to a jeweler in Harve, Mont.9] She admitted they were hers. Then her purse was taken and from it were taken several rolls of $20 and $10 bills. She admitted they were there when she was arrested.… All of the bills in her purse bore signatures purporting to be of the officers of the bank to which the bills were issued. When arrested she told Detective Shevelin that she forged the names of the bank officers.”

According to the report, she confessed that the man Logan was actually Harry Longabaugh, and that he was one of the men who robbed the Great Northern express. Otherwise, she refused to talk, so Desmond had Logan (actually Ben “The Tall Texan” Kilpatrick) taken to his office. The report continued with Desmond’s questioning of Logan (Kilpatrick):

“‘This woman says that you are one of the train robbers and that your name is Longabaugh,’ said the chief.

“‘She lies,’ said Logan.

“‘She claims that you gave her the money, but that she signed the bills,’ said Desmond.

“‘Yes, I gave her the money, but I found it out West. Had nothing to do with the train robbery,’ said Logan. He refused to say where or under what circumstances he found the money.”

Logan was described as a “powerful man” over six feet in height and weighing 200 pounds.

“His arrest was made in a resort on Chestnut street, and was accomplished by a ruse. Two detectives who had been trailing him entered the house shortly after he did, and feigning to be intoxicated, staggered into the parlor where the suspected bandit was sitting. One grabed [sic] him by the right wrist, the other by the left, and each pulled a big revolver from his hip pocket, with which they covered the bandit, when he surrendered, without a struggle.

“When taken to the Four Courts and searched he was found to have on his person $60 of the stolen bank notes. He remained sullen all day and answered questions in a monosyllable or not at all, as seemed to suit him.

“A dispatch from Nashville says a man answering the description of the prisoner passed several of the worthless notes there recently, and when detectives attempted to arrest him fought his way out and stealing a horse, fled. He was pursued and bloodhounds put on his track, but the next morning two of the dogs were found dead, having been shot with a revolver.”

The woman eventually admitted that she was Laura Bullion and that her home was in Knickerbocker, Texas.

“Her grandparents, Byerly by name, she said, reside at Douglas, Ariz. The woman laid great stress upon the respectability of her grandparents and begged of the officers to withhold the fact of her arrest from them. Chief Desmond is of the opinion that Miss Bullion, disguised as a man, actually participated in the express robbery.”

They would find $7,000 of the missing loot on Kilpatrick and another $9,000 was said to have been taken from Kid Curry when he was arrested in Jefferson City, Tenn., not far from Nashville.

In November 1902 the Kid was convicted on 10 of 19 counts for forging signatures on the stolen notes and passing and possession of stolen notes. He was sentenced to 20 years in the federal prison in Columbus, Ohio, but in June 1903 he escaped prior to transfer.10

“Deaf” Hanks, according to Wilson, had another $1,280 in the stolen money in a wallet he threw away in attempting to allude the law after tendering one of the $20s in a Nashville store.[11]

Wilson says another $440 was recovered after Hanks was killed by officers in San Antonio, Texas on April 5, 1902.

Ultimately, newspapers reported that $29,000 of the $40,000 in National Bank of Helena stolen notes were recovered.

The Union Pacific heist

There’s no doubt the spread of the information about the notes’ serial numbers helped link several members of the Wild Bunch to this robbery, but this wasn’t the only instance in which the Pinkertons were able to use serial numbers off of newly printed sheets to track these famous outlaws.

In an earlier train robbery, on June 2, 1899, the Wild Bunch held up the Union Pacific westbound train No. 1 near Wilcox, Wyo.[12]

According to the June 3, 1899 issue of the Idaho Statesman, Boise, Idaho, in a special report datelined June 2 to Cheyenne, Wyo.:

“At 4 o’clock this morning Union Pacific mail and express train No. 1 was held up one and one-half miles west of Wilcox station, in this state, by six masked men, who blew open the safe of the express car and carried away all the contents.

“The mail was not touched, presumably on account of the fact that four armed mail clerks were in charge.

“The mail and express runs as the first section of No. 1 overland limited. The second section follows five minutes behind. A bridge two miles from the scene of the robbery was fired to prevent the second section from coming up during the operations. A bridge in front of the train was dynamited.

“The train men were all covered with rifles and the robbers took their time. The value of the plunder is unknown but it’s represented as light. The sheriffs of Albany and Carbon counties, with posses and United States marshals, are after the bandits, who are supposed to be members of the notorious ‘Hole in the Wall’ gang which has terrorize the state for years.”

The newspaper further detailed that Union Pacific officials first received information about the robbery from engineer Jones. Jones reported:

“‘First section No. 1 held up a mile west of Wilcox. Express car blown open; mail car damaged. Safe blown open; contents gone. We were ordered to pull over the bridge, just west of Wilcox, and after we passed the bridge the explosion occurred. Can’t tell how bad the bridge was damaged. No one hurt except Jones, scalp wound and cut on hand.”

Additional reports suggested that the robbers boarded the train at Wilcox at 2:09 a.m. and when the “train reached the bridge, one of the robbers crawled into the cab and, at the point of a gun, ordered Engineer Jones to pull across the bridge and stop. Meanwhile the others of the gang were at work in the express car. Just as the engine pulled off the bridge there was a tremendous explosion that scattered the express car for a hundred feet in every direction. The end of the mail car was blown in and several stringers knocked out of the bridge, Engineer Jones was slightly injured by the flying debris.

“It only required a few minutes for the robbers to rifle the safe, which was blown open by the explosion. They took its contents, signalled their confederate on the engine, and before the passengers and train crew were aware of just what happened, were off for the mountains. It required two hours to clear the wreck away so that the train could proceed to Medicine Bow, the next station, from which the report was sent. The sheriff was notified and with a posse started in pursuit of the robundefineders.”

A mail clerk, W.G. Bruce, further related that when the robbers came to his car, they ordered him to open the door.

“When he refused to open the door, the robbers began shooting into the car from both sides. When the shooting commenced, Bruce turned out the lights in the car. Then a stick of dynamite was placed under the door and it was shattered. The clerks were also ordered out and fearing the car would be blown to pieces, opened the door. One of the robbers stuck his gun into the car and fired, but the bullet did no damage. The lights were then turned on and the clerks got out of the car.

“The clerks on the Portland mail car were also ordered out and the party of clerks and trainmen were stood up in a line and guarded by one man. A demand was then made of Ernest Woodcock, the express messenger, to open his car, but he refused. A couple of shots were then fired into the car and the door blown off.”[13]

The two passenger coaches were then detached and some of the robbers went to the back of the train and attempted, without success, to blow up the bridge behind it.

Next, “the express and mail cars were run down the track a mile or two, to the camp of the robbers. Then the trainmen were placed about 150 feet from the track and about 20 sticks of dynamite were exploded on top of the safe in the express car. The explosion completely wrecked the car and split the safe wide open. Five of the robbers carried away two loads each from the safe and must have secured a large amount of plunder. When the robbery was complete, the robbers walked leisurely up the hill north and disappeared in the darkness.”

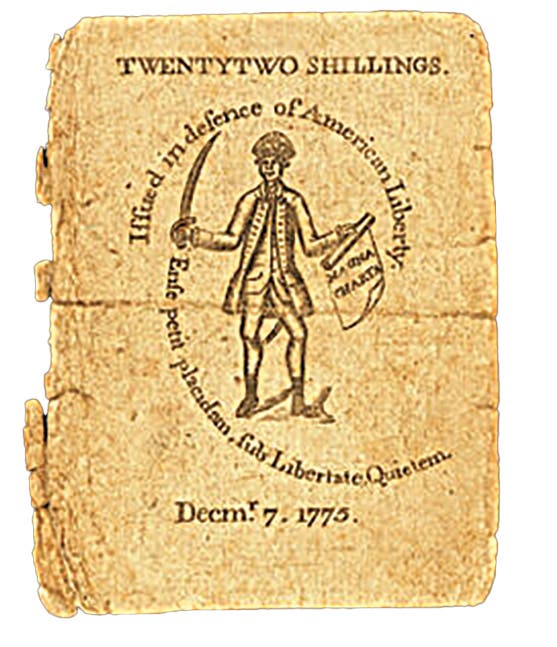

Mutilated bills

It was estimated that $36,000 in cash and $10,000 in diamonds were taken in the Wilcox train robbery, but a number of notes were destroyed in the explosion.

A reward of $2,000 a head was immediately offered by the Union Pacific and an additional $1,000 was added by the government.

The June 11, 1899 issue of the Dallas Morning News provided more detail on the missing loot and the serial numbers for the uncut sheets from the First National Bank of Portland:

“F.G. Chace, agent of the Pacific Express company, received the following yesterday:

“‘Fort Worth, Tex., June 9. – The Union Pacific westbound train No. 1 was held up near Wilcox, Wy. early Friday morning, June 2, and our safe blown open with dynamite and contents taken. Safe contained little besides one shipment of incomplete currency of $3,400 from the United States treasury department at Washington, D.C., for the First National bank of Portland, Ore. This was currency to be issued by the above bank and bearing their name, and incomplete, in that it lacked the signatures of the bank’s officers. There were twenty-two $100 bills and twenty-two $50 bills, Nos. 3705 to 3726 inclusive; also two $20 bills and six $10 bills, Nos. 5641 and 5642.

“We know that a part of this shipment was mutilated by the explosion as we have pieces of the twenty-two $100 bills and of the two $20 bills, said pieces being the lower right hand corner including the seal. The remaining twenty-two $50 bills and six $10 bills may be more or less mutilated.

“If an attempt is made to circulate any of the above described bills, gain all information possible and promptly notify the undersigned. O.W. CASE, superintendent.”

According to one newspaper account, “The [serial] numbers of these notes were sent to every police authority, postoffice and bank in the country.”[14]

A wanted poster from the Pinkertons gave a breakdown, including the plate positions:

• 22 $50 notes, bank Nos. 3705 to 3726 inclusive, plate position A; treasury Nos. A744372 to A744393 inclusive;

• 22 $100 notes, bank Nos. 3705 to 3726 inclusive, plate position A; treasury Nos. A744372 to A744393 inclusive;

• Two $20 notes, bank Nos. 5641 to 5642 inclusive, plate position A; treasury Nos. T130922 to T130923 inclusive;

• Two $10 notes, bank Nos. 5641 to 5642 inclusive, plate position A; treasury Nos. T130922 to T130923 inclusive;

• Two $10 notes, bank Nos. 5641 to 5642 inclusive, plate position B; treasury Nos. T130922 to T130923 inclusive;

• Two $10 notes, bank Nos. 5641 to 5642 inclusive, plate position C; treasury Nos. T130922 to T130923 inclusive.

The First National Bank of Portland, Ore. received charter 1553 on Sept. 8, 1865. It issued Series of 1882 Brown Backs in 10-10-10-20 sheets and 50-100 sheets.[14] The amount of large-size on the bank outstanding as of 1935, according to Hickman and Oakes, was $661,466. In $10s and $20s the bank serials ran from 1-16131 and in $50s and $100s from 1-5437.[16]

It wasn’t long before the stolen bank notes began showing up. The March 5 issue of the Denver Post reported that six of the $20 bills had been encountered in an Arizona town.

The Jan. 18, 1900 Denver Rocky Mountain News, in a Jan. 17 datelined piece from Cheyenne, Wyo., added:

“The first clue was secured about December 1, when the Stockman’s National bank at Fort Benton received from Lonny Currey [Harvey Logan’s brother, Lonie] five $100 bills of the Portland bank to be forwarded for redemption, the lower right hand corner of each bill having been torn off. These bills were forwarded and found to be a portion of the large shipment made from the United States treasury and stolen at Wilcox. In the meantime the Cascade bank of Great Falls, Mont., got another of the same series of notes, giving a draft for them. When the source of these remittances was located the suspects got wind of the detectives’ movements and procured an outfit of horses and wagon, with a good supply of provisions, struck out through the wild unsettled region north and have now probably got beyond the Canadian frontier.”

Under the headline, “Robbers Putting Plunder in Circulation,” the July 31, 1899 Denver Rocky Mountain News reported in a special from Casper, Wyo., dated July 30 that: “Several unsigned bank notes consigned to a bank at Portland, which were taken by the Union Pacific train robbers at Wilcox last month, have been discovered in circulation at Thermopolis. So far two $10 bills, one $20 bill and one $50 bill have been detected, all unsigned.

“There is hardly any question but that the three robbers who were pursued from Casper to the Wind river country, are still hiding in the Hole-in-the-Wall country or neighborhood, and that their friends are circulating the unsigned bills. It is hardly probable that the bills of the same bank to which the signature was forged, which were discovered in Denver last week, are being circulated by the friends of the three robbers, who were chased to the wild and rugged country in central Wyoming, but it is thought to be done by the other three robbers, whose escape from the scene of the robbery has always been a mystery to the officials.”

The Jan. 18, 1900 Denver Rocky Mountain News wrote:

“Further particulars have been received here regarding the Union Pacific train robbers, who have been trailed to Harlem, Mont. A bulletin just sent out by the Union Pacific road says satisfactory evidence has been obtained that the Curry brothers are part of the gang which held up and robbed the train at Wilcox, Wyo., in June last. Each of these men is fully described in the circular. Their names are Louis or ‘Lonny’ [Logan], ‘Bob’ [Lee] and Harvey [Logan]. Louis has been running a saloon at Harlem. He suddenly sold out January 7 and skipped the town with Bob, both being heavily armed. It is thought they have been joined by Harvey and have possession of a part or all of the $3,400 unsigned bills of the First National bank of Portland, Ore.

“The reward offered by the railroad and express companies—$3,000 for each party captured, is still in force, and they are being closely pursued by the officers and detectives employed on the case.”

Some writers argue that Butch Cassidy was one of the bandits, but others say he may have only been around for the distribution of the loot. Those believed to have been involved in the robbery itself include Kid Curry, his brother Lonie, and “Flat Nose” George Currie.

Beginning of the end

In 1905, reporting that the Hole-in-the-Wall was losing its tenants, the Jan. 29 issue of the Fort Worth (Texas) Star-Telegram prematurely eulogized on the end of the Wild Bunch and an era, but detailed several of the Wild Bunch’s deeds and fates in an article that in its day surely made for scintillating reading. At the time of the article, it was incorrectly believed that a body that had been found was that of Kid Curry. The newspaper wrote:

“The end of the ‘wild bunch’ has been announced to a relieved northwest more than once. When Logan was found self-killed an enthusiastic sheriff wired to a Chicago detective agency whose work had been onerous in Wyoming and Colorado: ‘Dead robber absolutely identified as Logan. This means the end of the Hole in the Wall gang.’ In the minds of the thief takers and men tamers of the west, Harry Logan, who was better known as ‘Kid Curry,’ was the leader of that band: ‘the Hole in the Wall’ without Logan would surely become but a memory of wickedness. To that versatile outlaw had been credited the leadership of the ‘bunch’ that robbed the Butte county bank at Belle Fourche, S.D., in 1897; that held up a Union Pacific train at Wilcox, Wyo., in 1899; that robbed the First National bank at Winnemucca, Nev., of over $30,000 in 1900, and that got $35,000 from a Great Northern train at Wagner, Mont., in 1901. By the time he was run to earth it was thought that the ‘wild bunch’ had dwindled to ‘Kid Curry’ and two others. It was known that ‘Butch’ Cassidy (sinister, fitting name) and Harry Longbaugh [sic], the ‘Sundance Kid’ were at large, but it was thought that they had deserted ‘The Hole in the Wall’ forever.… For fifteen years, at least, ‘The Hole in the Wall’ has been known and used by the outlawed among the cowboys and gamblers of the northwest. It was in 1892 that its secrets were revealed to the world. In that year a Northern Pacific train was held up near Big Timber, Mont., and the express car plundered. The ‘job’ was well done, and the posse formed to run down the robbers had a long, stern chase. One man, Camilla Hanks, was captured [he would be killed in 1902 by law officers in a saloon in San Antonio[17]]. He was the ‘Deaf Charlie’ of the gang, and from him the officers got the first trustworthy information concerning the ‘wild bunch.’ He was from Texas, as was Ben Kilpatrick, the ‘Tall Texan,’ who was neatly trapped by detectives while on a drunken spree in St. Louis. After serving a ten years’ sentence at Deer Lodge, Mont., he returned to the old life, to be killed two years ago by a posse at San Antonio.”

The Kid’s death place and date of death has never been established beyond doubt. Like Butch and Sundance, some said he went to South America, but the stories of his and those of Butch and Sundance reliving their glory days in another land seem to be as riddled as the many tales of their ultimate demise.

As to the ladies, their fate was better. Laura Bullion spent time in prison in Jefferson City, Mo. for her part in trying to spend The National Bank of Montana notes. She lived her last years in Memphis.[18] Annie Rogers, the woman who walked into the Memphis bank at the beginning of this tale, was convicted but acquitted in June 1902. She reportedly lived well into the 1920s.

Perhaps, some day examples of the Wild Bunch loot will be found. But the likelihood is that all have vanished with the passing of the once wild West and expiration of its most notorious outlaws.

End notes

1 “Woman Robber,” Jackson Citizen, Jackson, Mich., Oct. 22, 1901.

2. Gary A. Wilson, Tiger of the Wild Bunch: The Life and Death of Harvey “Kid Curry” Logan, copyright 2007 Gary A. Wilson, Morris Book Publishing LLC, p. 131.

3. Ibid., p. 133.

4. Dean Oakes and John Hickman, Standard Catalog of National Bank Notes, 2nd edition, Krause Publications, Iola, Wis. 1990, p. 559.

5. Ibid., p. 558.

6. “Montana Money Must be Watched,” Times-Picayune, New Orleans, Oct. 9, 1901.

7. Oakes and Hickman, Standard Catalog of National Bank Notes, p. 558.

8. A Series of 1882 Brown Back $20 from the same bank appeared in the March 2014 Chicago Paper Money Expo auction by Lyn Knight Currency Auctions. It carries the name H. Dickenson as cashier.

9. Wilson, Tiger of the Wild Bunch, p. 133.

10 Ibid., p. 168.

11. Ibid., p. 148.

12. It’s a robbery depicted in the 1969 motion picture, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, starring Paul Newman, as Butch Cassidy, and Robert Redford, as the Sundance Kid. Katharine Ross played Etta Place. Little is known about Etta Place other than that she is famously pictured with Sundance in New York in 1901 just before the pair embarked for South America.

13. Lightning would strike twice for the unfortunate Charles E. Woodcock, as he was aboard a second train robbed by the Wild Bunch. This one was at Tipton, Wyo., on Aug. 29, 1900, as loosely depicted in the 1969 movie, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.

14. “Pinkertons Get the Third,” Denver Post, Denver, Colo., March 1, 1900.

15. Hickman and Oakes, Standard Catalog of National Bank Notes, p. 884.

16. Ibid.

17. Wilson, Tiger of the Wild Bunch, p. 163.

18. Ibid., p. 20

This article was originally printed in Bank Note Reporter.

>> Subscribe today or get your >> Digital Subscription

More Collecting Resources

• The Standard Catalog of United States Paper Money is the only annual guide that provides complete coverage of U.S. currency with today’s market prices.

• If you enjoy reading about what inspires coin designs, you'll want to check out Fascinating Facts, Mysteries & Myths about U.S. Coins.