Bank notes once way to commit fraud

By Q. David Bowers Wolfeboro (spelled Wolfborough without the “e” in the early days) has had many banks over the years. Remarkably, for a town of about 6,300 citizens today,…

By Q. David Bowers

Wolfeboro (spelled Wolfborough without the “e” in the early days) has had many banks over the years. Remarkably, for a town of about 6,300 citizens today, we have four banks: People’s United, Citizens (scheduled to move into a new building next to Town Hall), TD North and Meredith Village Savings. All of these are based out of town, and TD North is headquartered in Canada. All are regulated, and all operate on a sound basis.

This was not always so.

In New Hampshire in the early days, banks were set up by state charter. The first was the Portsmouth Bank in 1792. Stock was offered and sold by the officers and directors who formed banks. It was supposed to be paid for in specie (gold or silver coins), but, in reality, most purchasers paid in bank notes or even in promissory notes. There was no oversight, there were no regulations, and bank officers conducted business as they pleased.

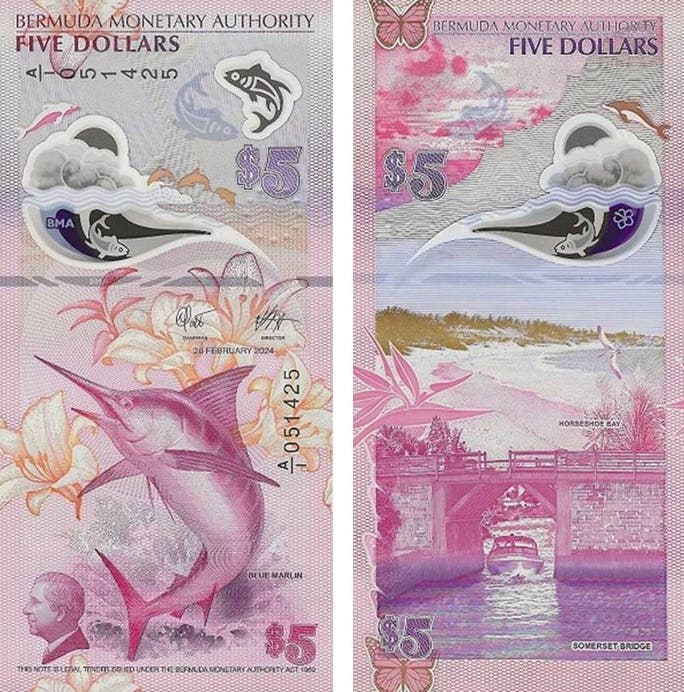

Bank notes were issued with the name of a given bank, a date, serial number, and the inked signatures of the cashier and president. Although banks were not supposed to issue notes in excess of their paid-in capital, many did. The various bank-note printing companies delivered whatever quantities banks ordered. No questions asked.

In New Hampshire, most banks were conducted responsibly. There were quite a few exceptions, however. Gaming the system, unscrupulous officers ordered large quantities of notes, signed them, and then sold them at deep discounts to brokers and speculators in distant places. The notes were placed into circulation with the realistic expectation that most would never find their way back to New Hampshire to be redeemed in silver or gold coins on demand. Most such banks did not have enough such coins anyway.

One of the largest bank scandals in American history took place in the first decade of the 19th century with the Hillsborough Bank of Amherst, New Hampshire. The bank issued huge quantities of worthless notes and shipped them to speculators as far distant as Ohio. It collapsed in fraud in 1807 and 1808. No one was ever prosecuted, and the bank’s president, Samuel Bell, was later elected as the governor of our state! Needless to say, his official biography neglects to mention his criminality!

Turning now to our town, on July 5, 1834, the Wolfborough Bank was established by a group of leading citizens including, alphabetically, Samuel Avery, Adam Brown, William H. Copp, Samuel Fox, James Hersey, Samuel Leavitt, Henry Parker, Joseph L. Peavey, Daniel Pickering, Aaron Roberts, Henry B. Rust, and Thomas Rust. Daniel Pickering, who has been mentioned in this column many times, years later in 1850 opened the Pavilion Hotel in Wolfeboro. The State Legislature allowed the bank to capitalize at $100,000, a very generous sum for a small-town bank.

Directors were all local men of sound reputation: Nathaniel Rogers, Samuel Avery, Joseph Hanson, John P. Hale, Daniel Pickering, John Williams, and Thomas E. Sawyer. Daniel Pickering was president; Thomas E. Sawyer, cashier. Subsequently, Augustine D. Avery became cashier, and later Thomas Rust served in that post.

Subscription books were opened for the stock, but money in town was very scarce. Relatively few shares were sold here. Sensing an opportunity, some well-intentioned investors in Dover, a center of manufacturing wealth, bought shares. On the dark, indeed dismal side, some sharpers in New York City viewed the new and somewhat troubled bank as ideal for a scam.

Bills signed by reputable Wolfeboro men would surely be well received in distant places. Our town was remotely situated regarding transportation. It was years before there was railroad service to the other side of Lake Winnipesaukee, ditto for passenger steamship service in warmer months. There was little likelihood that someone holding a Wolfborough Bank bill in, say, Philadelphia would ever try to redeem it. Instead, such a bill and others were simply passed on in the channels of commerce. Profits were unlimited!

Making matters worse, most bank stock was paid for in promissory notes. The iron safe in the Bank Building (still standing; KellerWilliams Real Estate run by Adam Dow is there today) had very few coins with which to redeem bills if requested. As if that wasn’t enough, the financial Panic of 1837 swept the country, resulting in the closure of thousands of businesses and many banks. Conditions were tough in Wolfeboro as they were elsewhere, but local activities persevered, and there was no great hardship. At least, in extensive research I have not learned of such. The bank officers and their families remained prominent and well-respected.

Financial circumstances soon overwhelmed the bank. It closed its doors. Finally, the State Legislature in Concord took notice, and in the late 1830s a banking commission was organized. An audit of the Wolfborough Bank on June 1840 showed that bonds and promissory notes given for bank stock in the amount of $141,066.93 were essentially worthless. Fraud was alleged, and investigations continued.

Unknown huge quantities of the bank’s paper money remained in circulation in the hands of people outside of New Hampshire.

In 1842, the state appointed Thomas Rust, a prominent citizen of Wolfeboro, to be the cashier, to try to manage what was left. That was not much. Total assets amounted to only about $150. There were no records of the quantities of notes issued.

One might think that by 1842 the bank was history. But, no! Fraudsters in New York City continued to order large quantities of Wolfborough Bank notes, to be delivered directly to them and signed with forged and even fictitious signatures!

Then, in 1849, sharpers in New York City attempted to reorganize the bank with another State of New Hampshire charter, with no intention of actually engaging in legitimate banking, and fraudulently float a new issue of paper money. The attorney general of our state was instructed to proceed against the action. It was related that:

“Various attempts have been made by persons from abroad to reorganize the bank and procure a new issue of its bills – that William Ingalls and Asa Hinckley of New York, are now engaged in such an attempt, having visited, and proposing again to visit Wolfborough for that purpose – that at Ingalls’ request, at a meeting convened and attended by him, a board of directors was chosen, consisting of John H. Wiggins, Esq., of Dover, president; John Peavey, Samuel Bean, A.L. Hersey, Nathan Bailey, George W. Libbey, and Henry Sayward. Hersey alone was the holder of any stock. The rest held no stock whatever and yet assumed to elect one of their number president of an institution with which they had no connection, upon a mere assurance from Ingalls that he would convey to them a share of stock each, which, however, has not been done.

“Mr. Rust further deposed that he had reason to believe that Hinckley and Ingalls had procured new bills of the Wolfborough Bank to be engraved and printed. From another reliable source, ‘I had evidence that the said Wiggins had signed certain of these bills as president, but had declared his intention to keep possession of them until they might properly be issued.’”

Not aware of what was actually happening, respectable local citizens lent their name to such efforts, hoping that, indeed, our town would have an operating bank that would serve local commerce. Extensive investigations continued into the 1850s. The state officially concluded that Wolfeboro citizens who were involved may have been imprudent (to say the least!), but none were involved in falsifying records and distributing large quantities of unauthorized notes.

None of the New York City criminals were ever prosecuted. One of them, Samuel Dakin, was involved in other fraudulent banks as well. Thus ended the first chapter in the history of Wolfeboro banking and the first of several financial scandals the town would experience over the years.

Today, the notes of the Wolfborough Bank are seen with some frequency on the collectors’ market, nearly always with fake signatures, and typically sell for $200 to $300 or so, if intact and not damaged. Ironically, all are worth far more than the original face values printed on them, usually $1 to $5 denominations!

This story by Q. David Bowers was published Sept. 21, 2017, as his column, “Looking Back,” in the “Granite State News.” There it was called “The great Wolfborough Bank scandal.” It appears here courtesy the author and the newspaper.

This article was originally printed in Numismatic News Express. >> Subscribe today

More Collecting Resources

• The Standard Catalog of United States Paper Money is the only annual guide that provides complete coverage of U.S. currency with today’s market prices.

• Subscribe to our monthly Coins magazine - a great resource for any collector!