Clairton National Banks Boom

Welcome to the New Year and the beginning of another set of the tours of small towns and their national banks for which you have become accustomed. This month we’ll…

Welcome to the New Year and the beginning of another set of the tours of small towns and their national banks for which you have become accustomed. This month we’ll be visiting Clairton, Penn. Though at one time called the “Coke Capital of the World” for its steel producing capacity, Clairton has fallen on hard times and has turned quite ghostly.

Clairton is a city of roughly 6,500 in Allegheny County that sits on the meandering Monongahela River about 15 miles as the crow flies southeast of Pittsburgh. It is easily reached via State Route 837 (along the river) or State Route 885. Clairton’s existence began just after the turn of the 20th century when the United States Steel Corporation acquired a large tract along the west side of the Monongahela River; this became the site for an integrated steel mill and coke production facility, which eventually became one of the world’s largest. The site had more than a thousand acres of level land suitable for a large industrial complex. On April 12, 1903, Clairton was incorporated as a borough.

During the next several decades, growth and advancement indicated a thriving city. As the steel mill and coke production facilities expanded, the population of Clairton grew. Clairton took on a life of its own, including a business district and educational, religious, and cultural facilities. The city peaked in the late 1950s when the population approached 25,000.

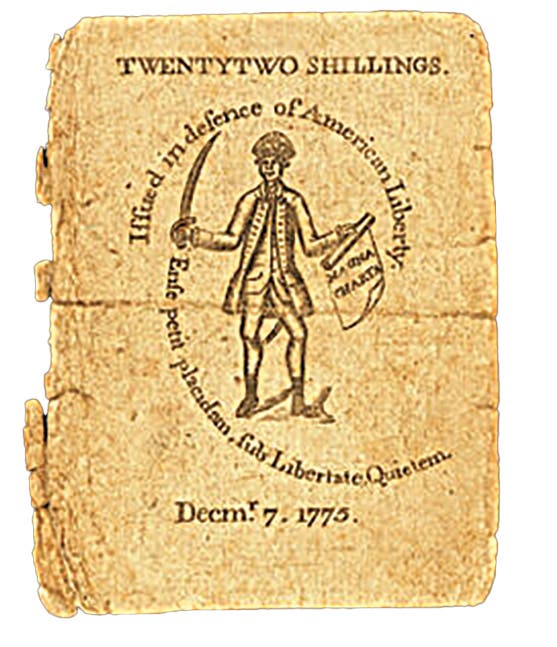

Naturally, this type of rapid industrial growth necessitated a national bank, and thus the Clairton National Bank was chartered in late 1902 and received charter #6495. Surprisingly, given the town’s growth and potential, this bank only lasted 8 years, liquidating in February 1910. Its issue, consisting of Series 1902 Red Seals and Date Backs, was a very small $81,000. Notes from this bank are quite rare—just 5 are known, all of them Red Seals.

For years, the only notes known from this bank were from the same uncut sheet of $5 Red Seals, bearing serial #226. I used to own this sheet, and an interesting story surrounds it. About 25 years or so ago, at the Memphis International Paper Money Show, I was sitting at a table late on the opening day. Most of the dealers had closed for the evening. From behind and a few tables down, I overheard a conversation that piqued my interest. I turned to look and saw a dealer and customer discussing an uncut sheet of Red Seal notes. Mind you, uncut sheets were frequently available at the time, and Red Seals, while desirable, had not achieved the notoriety they enjoy today.

The prospective buyer was going on about how the sheet had many folds, and how the price was too high, etc. The tabled dealer seemed a bit exasperated; eventually the prospective buyer indicated he would think about it and moved on. I decided to have a look. I examined the sheet, which indeed had been folded and handled, but was attractive enough with lovely pen signatures on the notes. At the time, everyone was using Don Kelly’s “National Bank Notes, Second Edition” (1985), which unlike more modern versions did not have actual values for notes, just “premiums.” I noticed that the “premium” for Red Seals on this bank was “$300+”, which was quite high given that premiums of “$20+” and “$35+” were the norm for large size Blue Seal notes from many banks.

Accordingly, I inquired about the price, and soon we were able to come to a deal—part cash and part trade for items in my showcases. Early the next morning the dealer came to my table and picked out a few items; I paid the difference, and the sheet was mine—much to the chagrin of the previous haggler who came back looking for it only to find it had been sold!

Back in those days it was quite common for dealers to cut up uncut sheets, based on the adage that it was easier to find 4 buyers for a note than it was to find one buyer for 4 notes. Accordingly, I cut the sheet and sold two of the notes to a major collector of Pennsylvania notes, where they continue to reside in his sophisticated collection. Though I have not cut many large size sheets myself, I have made it a practice to always keep one note from any sheet I do cut, with the top or bottom selvage attached (I really like notes with selvage and continue to buy them). I saved the bottom note from the sheet for my collection; the fourth note was auctioned off later and I don’t know where it currently resides.

Those 4 notes remained the total population known from the Clairton National Bank until about 4 years ago, when a lower grade circulated Red Seal note turned up; it eventually made its way into Jesse Lipka’s hands and was later sold in Lyn Knight’s Sale of Red Seals from Lipka’s collection. I have included a photo of my note—the bottom note from the now cut sheet. Note the wonderful pen signatures of L.W. Birmingham, cashier, and W.W. Payne, vice president.

Down the hill from Clairton was the small town of Wilson, and as Clairton grew, the line of distinction between the two towns blurred. Wilson had its own bank, the First National Bank of Wilson, charter #6794, which opened in 1903. On Jan. 1, 1922, the city of Clairton absorbed the town of Wilson, and accordingly, the bank changed its name to the First National Bank of Clairton. This bank continued to do business in the old Wilson building, and also moved into the former Clairton National Bank building. This bank survived the end of the national currency era, issuing a total of $568,000 in notes under the two titles. Just a single Red Seal note is known under the Wilson title; half a dozen large and nearly 20 small notes are reported under the Clairton title. I have included a photo of a small size note issued by this bank.

One interesting aside about Clairton is that the city was the setting for the movie The Deer Hunter (1978), although none of the movie was actually filmed there (other mill towns in the Monongahela River Valley and elsewhere in the tristate area were used). Even the opening scene, which features a large sign saying “Welcome to Clairton, City of Prayer,” was shot in Mingo Junction, Ohio.

Clairton today is just a shell of its former self. Steel mills still exist, on a much smaller scale, and the town is withering. We rode through the main part of town and found the old Clairton National Bank building on the corner of St. Clair and Miller Avenues, next to the Croatian Club. A classic three-story structure with an arched entranceway and fancy arched second floor balcony, the building today houses a few apartments and a Pizza Uno restaurant in the main lobby.

I rode the streets of Clairton and saw street after street of vacant storefronts and abandoned shops. Though the City of Clairton web page describes the town as “a thriving community …filled with hardworking young professionals, busy families and active senior citizens… offer(ing) affordable housing, a diverse school system, a quaint public library, a vibrant senior citizen center, lively recreation programs and a variety of dynamic churches,” the Clairton we saw showed little of that. I have included a couple photos to illustrate the point: the hardly inviting “Hotel Clairton” on St. Clair Avenue, with its weathered façade and broken windows, sits alongside vacant storefronts.

Nearby along Route 837 in the Blair district, just up the street from the steel mill, was a row of abandoned bars and storefronts, more reminiscent of a western ghost town than an East Coast steel city. The buildings were vacant and vandalized, an entire abandoned row that belied Clairton’s once prosperous, but now dead, past. One building worth seeing, however, was Clairton’s art-deco style post office, erected in 1930 and still in operation. It is rare to find nice art-deco architecture well preserved these days.

Further down State 837 was the heart of old Wilson, and the old bank building was still standing on the main corner. I had a vintage photo postcard, circa 1910, with me, and the building still looked much the same. On the north side, one could still make out a faded advertisement for the First National Bank of Clairton painted on the building. Today, the building houses some apartments on the upper floors and the Wilson Civic Association Civic Center on the street level.

Clairton’s ghostly remains and abandoned storefronts were quite appealing to the ghost town enthusiast in me. Clairton is easy to find, reasonably safe during the day and worth picking around if dying towns interest you as they do me.

Readers may address questions or comments about this article or national bank notes in general to Mark Hotz directly by email at markbhotz@gmail.com.