Creation of Money by the Aldrich-Vreeland Act of 1908

An explanation of the mechanism in the Aldrich-Vreeland Act that allowed for the creation of additional national bank notes.

Purpose

The purpose of this article is to explain the mechanism in the Aldrich-Vreeland Act that allowed for the creation of additional national bank notes in order to add elasticity to national bank note circulation. The Aldrich-Vreeland Act is the act that authorized the Series of 1882 and 1902 dates back to national bank notes.

Aldrich-Vreeland Act and Elasticity

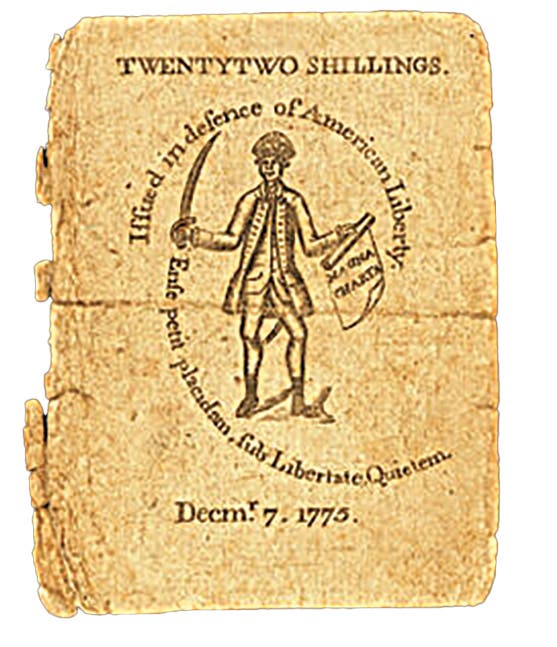

The Aldrich-Vreeland Act, often called the Aldrich-Vreeland Emergency Currency Act, carried the innocuous official title of an Act to amend banking laws. It was passed on March 30, 1908, in direct response to the ruinous Panic of 1907. That panic, caused by the collapse of a stock market bubble, brought our economy to its knees and reverberated around the world. It resulted in bank failures across the country that swallowed the then-uninsured bank accounts, thus wiping out a significant fraction of the wealth of our emerging middle class.

One monetary concern at the time was the national currency, which proved to be flawed because it was inelastic. Inelastic meant that the volume of national currency in circulation was unable to expand and contract to accommodate seasonal fluctuations in the demand for currency or to adjust to mitigate economic shocks to the economy that required liquidity. The result was seasonal swings in interest rates that punished borrowers just as they needed loans. Worse, when monetary shocks hit, panicky depositors withdrew currency from banks just at the time that the bankers needed increased liquidity to counter the bad news.

The problem with national currency was that the quantity was tied by law to the capitalization of the banks, a number that was static over the short term and thus unresponsive to the economy. At the time the Panic of 1907 came along, the maximum amount of circulation a national bank could issue was dictated by a provision in the Gold Standard Act of March 14, 1900. Specifically, the circulation could not exceed 100 percent of the paid-in capital stock of the bank. Consequently, the only way a bank’s circulation could be increased was to increase its paid-in capital by raising money from its stockholders just at the time they were most likely trying to increase their own liquidity to respond to the unfolding economic downturn.

The problem of inelasticity had plagued national currency since its inception so national bank currency was increasingly reviled by economists and Treasury officials alike.

The popular name for the Aldrich-Vreeland Act comes from its sponsors, Nelson W. Aldrich, a Republican Senator from Rhode Island and its principal author, and Republican Representative Edward B. Vreeland of New York. Aldrich often was referred to deferentially in the press as the General Manager of the Nation and served in the Senate from 1881 to 1911. Co-sponsor Vreeland served from 1899 to 1913 in the House of Representatives. President Theodore Roosevelt signed the act the night it passed without a single favorable Democratic vote.

What was needed was a mechanism where the money supply could be boosted when needed but contracted as soon as the need passed. The idea floating around economic circles was to allow for the creation of additional national bank circulation when needed but tax the increase at a higher rate than traditional bond-secured circulation. Thus, when the need for it came along, the bankers and their borrowers would be willing to pay the higher interest rate to obtain it, but as soon as the need for it passed, the high-interest rates would cause them to liquidate the loans and drive it out of circulation.

The following is the essence of how the mechanism built into the Aldrich-Vreeland Act worked. Notice as you read this that the emergency infusion of money was created out of thin air using bank loans or non-Federal government bonded debt that the bankers obligated to the U.S. Treasury to secure the redemption of it. Notice further that the value of the loans and bonds put up to secure the emergency infusions was worth far more than the emergency money the bankers received, so they had a serious incentive to redeem it in order to recover their securities.

The Creation of Money and Elasticity

We are bankers in August 1914 operating under the current legal requirements in the 1908 Aldrich-Vreeland Act and 1914 amendment.

These allow us to accumulate commercial loans that have terms of four months or less that we fund with our depositor’s money as well as the operating capital of our bank. We obligate those loans as security to obtain emergency currency.

Let’s say these loans total $100,000. The Aldrich-Vreeland Act permits us to obtain 75 percent of the value of the loans in the form of emergency currency from the Comptroller of the Currency, specifically, $75,000.

The $75,000 was created out of thin air. We lend it as well, also in the form of short-term loans. Our portfolio of loans now stands at $100,000 using the bank’s money and $75,000 using the emergency currency.

Once the $100,000 in loans that we used as security for the emergency currency mature, we deposit $75,000 with the U.S. Treasurer so he can release the lien of the United States on those loans. The Treasurer, in turn, deposits the $75,000 into a redemption fund to retire the emergency currency from circulation. As it is presented, the Treasurer purchases it with the money in the redemption fund, and it simply vanishes.

When the $75,000 loan we made with the emergency money matures, that principal, coupled with the $25,000 we still hold from our original $100,000 in loans, leaves our bank with its $100,000 investment in the enterprise. The profits earned by our bank are the interest it earned on the $100,000 in loans it put up as collateral and the interest on the loans made with the $75,000 worth of emergency currency.

Yes, there were costs. The bank was paying interest on the part of the $100,000 that it used that came from its depositors and the interest it paid to the U.S. Treasury for use of the emergency currency.

What you have just witnessed is an example of monetary elasticity.

Outcome

The desired economic benefit was that some economic force was in play that was creating a shortage of money that caused interest rates to spike. Once those rates surpassed the threshold that triggered the economic viability of obtaining emergency currency, our bank stepped in and, through the mechanism provided, created an additional $75,000. This increase allowed us to not only serve our borrowers but simultaneously infused the economy with additional liquidity to deal with the monetary stringency that was fueling the interest spike. Thus, the newly created money was available to mitigate whatever was perturbing the economy, and its availability tamped down interest rates by reducing the competition for funds at the time.

The tax structure was as follows. The tax payable in January and July on the traditional six-month average bond-secured circulation of a bank was 1/4 percent each half-year if secured by two percent U.S. bonds or 1/2 percent each half-year for U.S. bonds paying more than 2 percent.

However, the tax on the emergency circulation in the original Aldrich-Vreeland Act was set at 5 percent per annum for the first month and 1 percent per annum for each additional month up to a maximum of 10 percent per annum. Obviously, there was no incentive for bankers to keep their emergency notes in circulation after the need for them had passed.

The fact was that the high tax on the Aldrich-Vreeland circulation set the bar too high, so no bankers took advantage of the act in its original form.

The act was originally set to expire June 30, 1914, but was extended to June 30, 1915, by an amendment hurriedly passed by Congress on Aug. 4, 1914, the day Britain declared war on Germany. The economic shock of the outbreak of war in Europe swept across the American economy as a liquidity crisis as the European nations cashed in American securities to raise money for their war efforts and exported our money.

The Aug. 4, 1914, amendment reduced the tax to 3 percent per annum for the first three months and 1/2 percent per annum for succeeding months up to a maximum of 6 percent per annum on the average amount of emergency currency that the bankers placed in circulation.

The first emergency currency was issued on Aug. 4, 1914, and the last on Feb. 12, 1915. The need for it quickly subsided, so by the time the Aldrich-Vreeland Act expired on June 30, 1915, all of it was being redeemed from circulation. However, when it was in use, the circulation of national bank notes spiked $386 million to an all-time record high of $1.1 billion.

Federal Reserve Notes

The Aldrich-Vreeland Act was passed in 1908. It was a monetary experiment. Serious work was being undertaken at the time by both learned men in Congress and the U.S. Treasury to somehow revamp U.S. currency to better serve the economy and to mitigate panics caused by economic shocks.

Visionaries saw a need for a currency that was anchored in the needs of economic activity in contrast to that of an arbitrarily set value attached to a stock of some metal.

Notice that the form of the elastic part of national bank note circulation built into the Aldrich-Vreeland Act was founded on loans and bonded debt, which were true measures of the ever-fluctuating need for currency. That model was not lost on the framers of the Federal Reserve Act of 1913. Consequently, the same mechanism became the basis for our Federal Reserve currency today.

Bankers now engage in a practice that is called rediscounting short-term commercial loans that they lodge with their Federal Reserve Bank. The discount is the difference between the value of the loans and the lesser amount of currency to be issued against them. The Federal Reserve Bank then issues currency to the bank. That currency is the grease that continually facilitates the movement of goods and services through our economy. The value of the money issued by the Federal Reserve Bank against the rediscounted loans is less than the value of those loans, which ensures that if some of the loans go bad, there will remain sufficient collateral to cover the value of the Federal Reserve notes issued against them.

Note that modern Federal Reserve notes are not secured by gold but rather by loaned money. It is fiat money created out of thin air that has value because it represents the obligations of millions of borrowers to repay loans that they are using to turn the cranks that, in real-time, are driving our economy and thus producing wealth. The idea was first introduced into our currency system in the Aldrich-Vreeland Act of 1908.

Now ask yourself, just what is money? That is a great philosophical question. It isn’t a piece of gold. If you are hungry and have a piece of gold, what good is it to you if there isn’t some market that will give you a Federal Reserve note for your gold so you can buy a hamburger at McDonald’s?