Don’t use overprinted signatures

by Peter Huntoon This is a tale of the fortuitous convergence of two disparate items within a couple of weeks of each other that reveals the seriousness that early Comptrollers…

by Peter Huntoon

This is a tale of the fortuitous convergence of two disparate items within a couple of weeks of each other that reveals the seriousness that early Comptrollers of the Currency attached to the bank signatures on National Bank Notes.

Lee Lofthus and I were digging through old Treasury files in the National Archives during August 2014 when Lee passed a letter over to me written by Comptroller John Jay Knox to the president of The Fourth National Bank in New York City. The letter is reproduced in total and it sets the stage.

Treasury Department

Office of the Comptroller of the Currency

Washington, April 10th, 1875

Sir:

I am informed that circulating notes of your bank have recently been placed in circulation with the engraved signature of the President and Cashier. Section 22 of the National Bank Act authorizes the engraving of the signatures of the Treasurer and Register, but not those of the Officers of National Banks. Sec. 23 of the Act provides that “After any such association shall have caused its promise to pay such notes on demand to be signed by the president or vice-president and cashier thereof, in such manner as to make them obligatory promissory notes, payable on demand, at its place of business, such association is hereby authorized to issue and circulate the same as money.” The construction of this Act is plainly that no National Bank has a right to issue circulating notes unless “signed” by the President or Vice President and Cashier thereof. This has been the interpretation of the Act by my predecessors in Office and the present Secretary of the Treasury concurs in the interpretation. I have therefore requested the Treasurer of the U. S. to transmit to this Office for destruction all circulating notes of your Bank with engraved signatures which may be returned to his Office for redemption and your Bank is directed to require that all circulating notes hereafter issued by your Bank shall receive the written signatures of your President or Vice President and Cashier.

If you have on hand any of your circulating notes with engraved signatures, you are requested to return them to the Treasurer for redemption.

Very Respectfully

John Jay Knox

Comptroller of Currency

P. C. Calhoun Esq Prest

Fourth Nat’l Bank

New York City

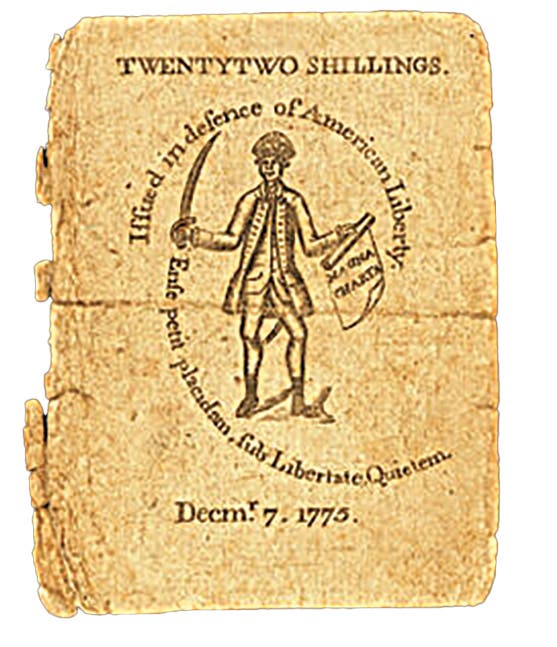

Shortly after I got home from the D.C. trip, Paper Money Guaranty received a very curious looking ace from The First National Bank of Woonsocket, R.I., with the penned signature of Jos. E. Cole scrawled vertically across the face. “Vice Pres’t” is neatly printed under it. Chad Hawk of PMG wanted to know what I thought of the note. I suspect that what lurked in the backs of everyone’s mind was if this represented some sort of defacement. But, the printed Vice Pres’t hinted at something more authentic—something legitimate. (see Fig. 2)

The other signatures on the Woonsocket note were Edward Harris, president, and Reuben G. Randall, cashier. The note was serial numbered in 1866 and those officers were current then. The big deal, though, is that Harris’ signature was printed on the note.

Probably the Woonsocket bankers had gotten a similar letter of admonishment for using overprinted signatures as Knox was sending to the Fourth National Bank or they read about the problem in some Banker’s Magazine article or Treasury circular. Their solution was to comply by having both the cashier and vice president hand sign their notes, but president Harris would still maintain his visibility as top dog with his overprinted signature even though he may not have been actively involved in the day to day operations of the bank.

What these bankers were saying is we’re going to print the busy or unavailable president’s signature on the notes to show who is president, but we’ll add the penned signature of the vice president to meet the requirement of the law. Now you folks in Washington go ahead and try to find some reason to repudiate our notes. There is nothing in the National Bank Act that says the letter of the law can’t be satisfied in this fashion.

At issue here was a significant fine point concerning the monetization of U.S. currency. Treasury currency of that era was deemed monetize when the Treasury seal was overprinted on the currency. However, National Bank Notes weren’t legally monetized until they were signed by the appropriate bank officials.

Two situations were causing problems. The most common was faded signatures. Less common were stolen notes with forged signatures. When these notes were rejected by the National Currency Redemption Agency, the unsuspecting note holder or a bank was stuck with the liability. These types of occurrences didn’t instill confidence in the currency.

Finally on July 28, 1892, an Act of Congress was signed into law that in effect nullified the importance of bank signatures. It stated: “That the provision of the Revised Statutes of the United States, providing for the redemption of national bank notes, shall apply to all national bank notes that have been or may be issued to or received by, any national bank, notwithstanding such notes may have been lost by or stolen from the bank, and put in circulation without the signature or upon the forged signature of the president or vice president and cashier.”

The gloves were off. Unless the note was a counterfeit, if it made its way to the National Bank Redemption Agency, it was going to be redeemed. It is at this point that you started to see the routine use of facsimile signatures that were applied using every means possible to do so.

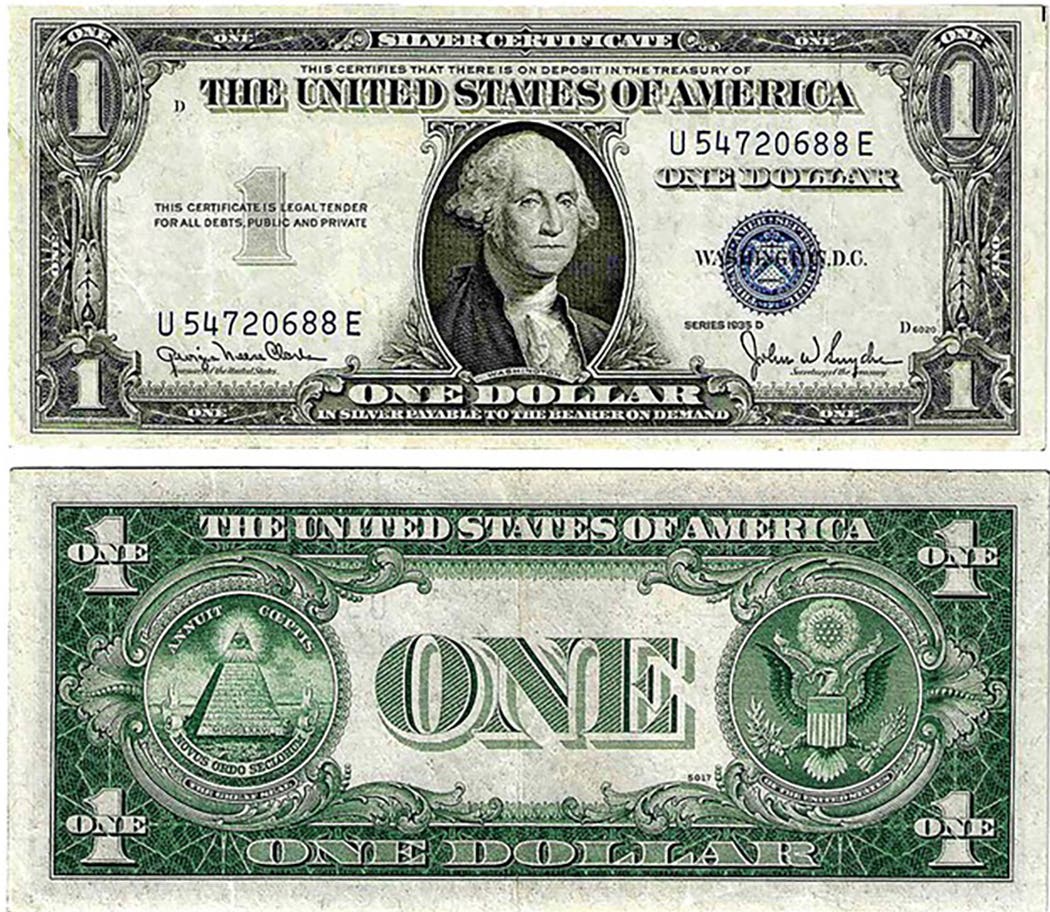

The case of The Fourth National Bank of New York City, the object of Knox’ letter, is poignant. The bank issued 555,412 notes in the Original Series alone. What president or even cashier of a major bank had time to sit around and sign all those. Clearly this was a point the framers of the National Bank Act had not thought through. The fact is, the officers at the Fourth National were having their signatures overprinted on their notes from the outset in 1864. You can imagine the annoyance occasioned by the receipt by them of Knox’ letter.

The Original Series $5 illustrated here is from the first printing of those notes (see Fig. 4). It carries the overprinted signatures of Calhoum and Seaman, whose signatures were current from 1864 to 1869. The $1 is from a printing in 1875 at the time Knox was chiding the officers about the practice. Calhoun and Lane’s signature combination was current from 1869 through 1881.

Other big city bankers continued to utilize overprinted signatures. A good example is the Series of 1875 $2 illustrated from Providence, R.I., with neatly printed bank signatures (see Fig. 5). That note was printed in 1877 and issued well before the 1892 act.

By the way, I think Joseph E. Cole’s signature splashed across the Woonsocket ace makes that note a particularly historic item because of the story it tells. It ranks up there with the neatest aces I have seen. Maybe other examples from that bank or other banks survive.

This article was originally printed in Bank Note Reporter. >> Subscribe today.

More Collecting Resources

• The Standard Catalog of United States Paper Money is the only annual guide that provides complete coverage of U.S. currency with today’s market prices.

• Keep up to date on prices for Canada, United States and Mexico coinage with the 2016 North American Coins & Prices guide.