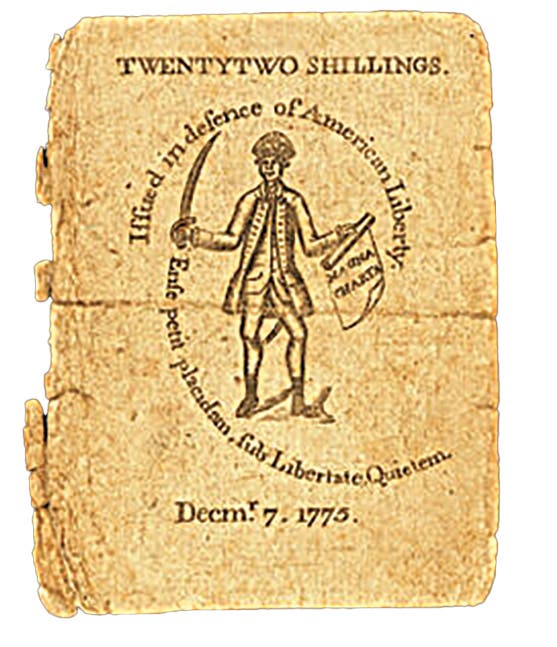

The very first U.S. paper money

Editor’s Note: Read more on this story here and here. By Peter Huntoon Salmon P. Chase, President Lincoln’s Treasury secretary during the Civil War, is, of course, the father of…

By Peter Huntoon

Salmon P. Chase, President Lincoln’s Treasury secretary during the Civil War, is, of course, the father of U.S. paper money.

The U.S. Treasury’s first circulating currency emissions were the Demand Notes authorized by the Act of July 17, 1861. Demand Notes were circulating promissory notes but they became as good as gold because Chase proclaimed in a Treasury circular that they would be redeemable in gold, which meant that the Treasury would accept them in payment for customs taxes that by law had to be paid in gold. Of course, the Treasury then did everything it could to remove them from circulation by replacing them with Legal Tender Notes when the legals came along.

The next type to come down the pike was Legal Tender currency authorized by the Act of July 11, 1862. They were nothing more than circulating Federal debt promising to pay the bearer a dollar of unspecified value at some unspecified future date. Their charm was that Congress declared them to be legal tender so everyone had to live with them, but during the Civil War they were discounted sharply against gold and their abundance led to high inflation.

The third type to arrive on the scene was national bank currency authorized by the Act of Feb. 25, 1863. Nationals also were fiat currency exchangeable into Legal Tender Notes, but the authorizing legislation had provisions that guaranteed that note holders would be able to redeem them in Legal Tender Notes even if the issuing bank failed. Consequently, the pretty things circulated although they were heavily discounted against gold identically to the Legal Tender currency into which they were convertible.

All these issues represented means and schemes floated by Chase and his patriotic allies in Congress in an attempt to give the Treasury sufficient liquidity that it could pay the costs of executing the Civil War, which averaged $2 million per day.

Chase was a staunch abolitionist and man of stellar integrity who possessed enormous ambition, drive, intellect and ego. He used his talents to guide the Treasury through the shoals of the Civil War with borrowing and the issuance of the greenbacks that fended it from bankruptcy. It seemed at times that the force of his personality alone saved the Union government from bankruptcy.

He had the ability to forge advantageous working alliances with movers and shakers in politics and finance. One key ally and friend was financier Jay Cooke in Philadelphia. Jay Cooke and Co. successfully mass marketed small denomination Federal Civil War bonds to the public appealing that it was citizens patriotic duty to buy them. Cooke went on to found The First National Bank of Philadelphia, charter 1. The fact that his bank received charter 1 was not a coincidence.

The Treasury never forgot Chase’s heroism during those dark days and rewarded his memory by first placing his portrait on $10,000 Federal Reserve Notes in 1918 and next on small-size $10,000 gold notes. Of course, he beat them to it by having his portrait placed on the $1 1862 legals so everyone could get the chance to see him as he aspired to become president.

In fact, he was a candidate for the presidency in 1860 when Lincoln ran the first time but Lincoln edged him out. Lincoln then kept political peace by appointing him to his cabinet—the team of rivals—as Treasury secretary.

As Lincoln was coming up for reelection in 1864, he cagily shunted Chase aside politically by appointing him chief justice of the Supreme Court. That prestigious plumb lifetime position, was so good, Chase couldn’t turn him down.

Ironically Chase then went on to lead the court majority in declaring the Legal Tender Act of 1862 unconstitutional in December 1869, a finding that was overturned in May 1871 by a more compliant court thanks to the timely appointment of two new justices by President Grant. At that juncture, Chase wrote the dissenting opinion affirming the court’s earlier stance.

Thus, the Legal Tender Notes survived and comprise the Red Seal small-size notes in your collections—and the unpaid outstanding Civil War debt that they represent. The Treasury and nation thank you for the patriotism you exhibit by squirreling them away.

Things did turn out OK, for with resumption of specie payments by the Treasury mandated by Congress to take effect Jan. 1, 1879, the Legal Tender Notes and the nationals linked to them became as good as gold even though at that moment the Treasury had only $1 in gold for every $4 in outstanding notes. But by then the war was won, the economy was moving, and it was in no one’s interest for a run to develop on the Treasury.

Three pieces of U.S. currency are known to have been saved by Chase, and in my opinion comprise the most historically significant of all the U.S. notes that are out there.

They are the first $10 Demand Note issued, the first $1 Legal Tender Note issued and a note from the first sheet of National Bank Notes issued. The best available photos that I could secure of them are reproduced here. All the notes were folded so Chase could carry them in his wallet and show them off.

Probably the $5 national heads the parade because in his own hand Chase penned on its back “First national bank note issued. S.P.C.” What more could you ask to tie a note to such history?

The numismatic provenance of these notes is a bit hazy. Martin Gengerke has done an admirable job in attempting to track their paths or at least their mention in the numismatic literature so I am reproducing his findings here:

• Fr. 17 - No. 1 $1 Legal Tender Note: Salmon P. Chase; George Blake; Chase Manhattan Bank 11/93; Hessler & Reinfeld Illus.

• Fr. 7a - No. 1 $10 Demand Note: Salmon P. Chase; Jay Cook; Sotheby 1970 Sale; John Ford; Mike Brownlee; advertised by New Netherlands Coin Co. in The Numismatist January 1971 as the first piece of U.S. currency issued, “POR” ($4,000); Phil Lampkin.

• Fr. 394 - No. 1 First National Bank of Washington D.C. $5: Salmon P. Chase; Sotheby 1970; John J. Ford; Phil Lampkin; Marc Watts; Mark Hotz.

Currently the $1 note’s whereabouts is unknown. It was not in the Chase Manhattan Bank collection when that collection was transferred to the National Numismatic Collection at the Smithsonian Institution.

The $10 is currently owned by a collector who wishes to be anonymous. Its story is the most convoluted of the three and the most controversial. Its debut on the numismatic scene certainly appears to be the 1970 Sotheby sale. How flamboyant Texas dealer Mike Brownlee fits into the chain is mysterious. Perhaps he and Ford agreed to share ownership of the note rather than run each other up against it when it appeared in the Sotheby sale. New Netherlands Coin Co. was Ford’s operation.

The New Netherlands ad in The Numismatist stated: “This particular piece of paper money * * * was personally presented to famous Philadelphia banker, Jay Cooke, by his close friend, Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase, as ‘the first U. S. greenback.’ It remained in the Cooke family for several generations, only recently finding its way upon the market.”

The New Netherlands attribution written by Ford appears to defy plausibility. At issue is the fact that both the Demand Note and Chase’s $5 national had just come from the Sotheby sale. How did both of them happen to miraculously get reunited for that sale if they had been in the estates of different families for the previous 100 years. Chase’s $5 is supposed to have come down through his family.

Gengerke credits Phil Lampkin with reuniting the pieces. Lampkin was a savvy Washington, D.C., area collector/dealer who liked high-end material. Veteran numismatist Julian Liedman, who knew Lampkin, did not recall seeing the note and doesn’t believe it was in his possession when he died and his remaining notes passed to his daughter.

If Lampkin indeed did have the $10, it is likely that he sold it before he died. Regardless, the route it took to its current owner is shrouded in the mists of time.

There is no question that renown collector/dealer George Blake, who was an early ferret of fancy serial numbers, once owned the ace. Smith’s biography of Blake stated that he exhibited paper money including a dollar bill Series 1, plate 1, serial 1, letter A” at the 1914 American Numismatic Association convention. How he got it is unknown, but the timing of his involvement with it strongly indicates that the piece was the first to leave the Chase family.

Whether Blake placed it with the Chase National Bank, forerunner to the Chase Manhattan bank, is unknown to me. It is likely because he circulated easily in New York banking circles as he pursued fancy serial numbers in new currency shipped to the New York banks and the Chase bank certainly would have had an affinity for the note. Telling is the fact that “On his last birthday, he [Blake] was featured on the advertisements of the Chase National Bank as its oldest living depositor” (The Numismatist, 1956).

Too bad Chase didn’t save the first $20 1863 Gold Certificate authorized by the Act of March 3, 1863. It would have made an excellent colorful representative of the fourth class of Federal currency to emerge during his watch. Who knows, maybe he did and it is still out there in the weeds.

I can’t certify the accuracy of the foregoing ownership attributions because I simply have no firsthand knowledge of the facts. There are gaps and ambiguities so I welcome additions that you might be able to provide. The problem, of course, is that the early numismatists who knew and may have handled the notes have been pushing up daisies for decades.

Sources cited

Gengerke, Martin T., on demand, U. S. paper money records, a census of U.S. large size type notes: CD produced on order, gengerke@aol.com.

New Netherlands Coin Co., Jan 1971, The first greenback!: The Numismatist, inside front cover.

Erlanger, Herbert J., March 1951, Metals of the New York Numismatic Club: The Numismatist, p. 271-272.

The Numismatist, February 1956, Obituaries, George H. Blake, LM 150: p. 166.

Reinfeld, Fred, 1960, A simplified guide to collecting American paper money: Hanover House, Garden City, N.Y. p. 128

Smith, Pete, 1992, American Numismatic Biographies, Blake, George H.: Gold Leaf Press, Rocky River, Ohio, p. 31.

This article was originally printed in Bank Note Reporter. >> Subscribe today.

More Collecting Resources

• The Standard Catalog of United States Paper Money is the only annual guide that provides complete coverage of U.S. currency with today’s market prices.

• Is that coin in your hand the real deal or a clever fake? Discover the difference with U.S. Coins Close Up, a one-of-a-kind visual guide to every U.S. coin type.