Gateway to History Through Tippecanoe City, Ohio

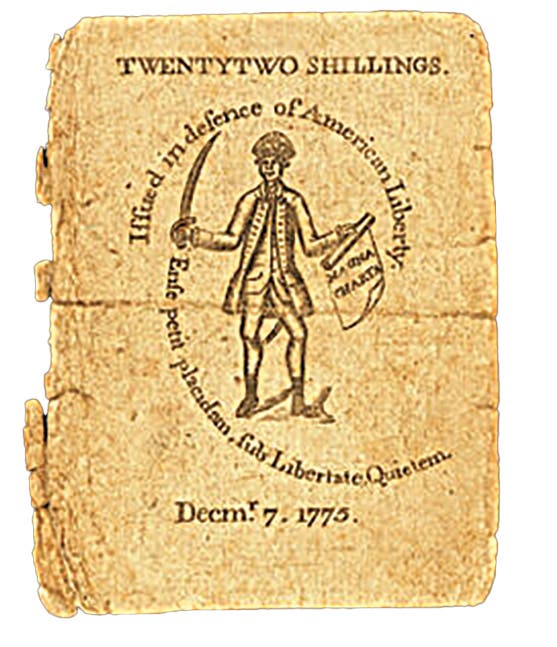

Of all the towns in Ohio for such a bank note to have survived, how can you beat Tippecanoe City?

Arthur Smith submitted this fabulous red seal as a candidate for this space, and I couldn’t get on it fast enough. There are so many threads from it; we’ll just have to see where it takes us.

Let’s top down, starting with the note itself. With the selvage, you know it was saved as a keepsake by one of the bankers. Scrawled in pencil in the margin is “signed July 6, 1907, first one.”

A quick look at the officers for the bank in the Comptroller of the Currency’s annual reports reveals that the cashier was Ahijah W. Miles, who served from the bank’s founding in 1883 through 1919. Thomas Corwin Leonard served as president from 1908 through 1932, so it is obvious that he stepped in as vice president in 1907, and this was the first sheet he signed. He went on to assume the presidency within a year, but this first note was the one he saved. This extra personalization on a national always raises my blood pressure.

At that time, the bank had a modest circulation of only $25,000. Both men signed this sheet using their best penmanship.

Leonard succeeded Jacob Rohrer as president. Rohrer held that position since 1891 and was Leonard’s father-in-law.

Of all the towns in Ohio for such a note to have survived, how can you beat Tippecanoe City? This is one of the most lyrical town names in the entire country, let alone Ohio! Why, it beats my former red seal from The Maiden Lane National Bank of New York. This has to be a town name with historical gravitas, and indeed, chasing it forced me to relearn some early American history I thought I could safely forget after the 8th grade.

Let’s disabuse you about the origin of the name of Tippecanoe at the outset. Its meaning has nothing to do with a capsized canoe. Tippecanoe City was founded in 1840 along the developing Miami and Erie Canal. It was named in honor of Presidential candidate William Henry Harrison, whose nickname was Tippecanoe. That nickname came down from his heroism at the Nov. 7, 1811 Battle of Tippecanoe in Indiana during his services there as governor.

It doesn’t matter what you learned about pre-Civil War U.S. history; the one thing you never forgot was the political slogan “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too!”—probably the most successful presidential slogan of all time. It won the 1840 presidential election for Harrison, the hero of the Battle of Tippecanoe, and Vice-President John Tyler for the Whig Party.

We’ve got to leave Ohio for Indiana to pursue both the origin of the word Tippecanoe and the Battle of Tippecanoe.

Tippecanoe is the name of a river in north-central Indiana near where the Battle of Tippecanoe was fought. Tippecanoe is the anglicized version of a Miami tribal term meaning “place of the succor fish people” because succor, also called buffalo fish, was abundant in the streams in the area.

As for the Battle of Tippecanoe, I lifted the following verbatim from an account written for the American Battlefield Trust.

"Indiana, Nov. 7, 1811: The Battle of Tippecanoe was fought between American soldiers and Native American warriors along the banks of the Keth-tip-pe-can-nunk, a river in the heart of central Indiana. Following the Treaty of Fort Wayne, an 1809 agreement requiring Indiana tribes to sell three million acres of land to the United States government, a Shawnee chief named Tecumseh organized a confederation of Native American tribes to combat the horde of pioneers flooding into native lands.

The organized resistance prompted Governor William Henry Harrison to lead roughly 1,000 soldiers and militiamen to destroy the Shawnee village “Prophetstown,” named for Tecumseh’s brother Tenskwatawa, “the Prophet,” and designed by Tecumseh to be the heart of the new Native American confederacy.

When Harrison arrived on the evening of Nov. 6, 1811, he was met with a white flag by one of Tenskwatawa’s followers, who requested a cease-fire and that the two leaders, Harrison and Tecumseh, parley before any action was taken. Such a parley would mean a delay, as Tecumseh was not at Prophetstown, having gone south to recruit warriors from the “Five Civilized Tribes” who were experiencing the same encroachment upon their lands.

A weary Harrison agreed to Tenskwatawa’s terms and retired his force to a hill about a mile from Prophetstown on the banks of Burnett Creek. Skeptical of the cease-fire, Harrison ordered his men into a rectangular defensive position for the night. Much of Harrison’s front lines were manned by militia, with 300 regulars in reserve to reinforce the untested militiamen if their lines faltered. The southern flank was covered by Captain Spier Spencer of the Indiana Yellow Jackets, a company named for the bright yellow overcoats that they wore into battle.

That night, Tenskwatawa was intent on breaking the cease-fire despite Tecumseh’s previous warnings not to incite war until the Confederacy was strengthened. He stood high above Prophetstown on a rock ledge now called Prophet’s Rock and riled his people into battle by singing war songs and chanting incantations that he promised would protect them from bullets.

At dawn the next morning, Harrison’s men were completely surrounded by Tenskwatawa’s warriors. The warriors made a diversionary attack on the northern end of the American rectangle, drawing the first shots of the battle and immediately waking the rest of Harrison’s sleeping force. Soon after, a fierce attack on the southern flank caused Spencer’s “Yellow Jackets” to waver and retreat after Captain Spencer and the two commanding lieutenants were felled by the swarming warriors.

Harrison was able to quell the chaos by transferring Captain David Robb and the Indiana Mounted Rifles from their position at the northern flank of the rectangle to reform the southern flank. The warriors grudgingly withdrew, and Harrison’s men were able to bolster their defenses.

However, the Braves then mounted a second wave of attacks, this time hitting both the northern and southern flanks of the rectangle. Again, the southern flank was engulfed in the most intense fighting, but the freshly reinforced lines were able to hold. On the northern flank, the second wave of attacks was met with stiff resistance as Major Joseph Hamilton Daveiss of the Indiana Light Dragoons led a countercharge to hurl back the advancing braves. As a result of his bold maneuver, Major Daveiss was mortally wounded and died shortly after.

Eventually, Harrison’s superior numbers and firepower carried the day, and the fighting ceased after two hours. Harrison and his force of mostly militiamen had held their positions and dispelled the warriors’ attacks.

Disheartened, the Braves returned to Prophetstown and discredited Tenskwatawa’s leadership and the spells that he had cast to protect them. The distrust for Tenskwatawa caused the Native Americans to immediately abandon Prophetstown, leaving it wide open for Harrison’s raid.

On Nov. 8, 1811, Harrison torched Prophetstown and began his long march back to Vincennes. Tecumseh returned to Prophetstown three months after the battle only to find it in ruins. It was the end of his dream of a Native American confederacy. The defeat at Tippecanoe prompted Tecumseh to ally his remaining forces with Great Britain during the War of 1812, where they would play an integral role in the British military success in the Great Lakes region in the coming years."

Who would ever think you would learn this stuff by looking into some guy’s national bank note?

Now, let’s get back to Ohio.

Tippecanoe City is located 15 miles directly north of Dayton and now has a population of about 10,000. However, it was renamed Tipp City in the 1930s by the Postal Service to avoid conflict with a tiny berg named Tippecanoe that lies 185 miles to the east in Harrison County, Ohio.

Acknowledging that modern Ohioans seem to wish to be perceived as a pious lot, they will admit in order to draw tourists that the early city was a popular stopping-off point for boatmen traveling the Miami and Erie Canal. The original downtown hosted a large number of bars and a red-light district. The now dry canal locks can be seen just east of downtown.

Development of the railroads in the 1850s and 1860s put the canals out of business and slowed the city’s rapid growth. Ruins of a repair shop for the old Inter-Urban rail system can still be seen on the outskirts of town.

The Tipp National Bank was organized in 1883 to serve the tamed successor community to this earlier history. What a killer note this is to have survived to provide a window on all of this, don’t you agree?

You may also like: