Inscribed Note Leads to Unique Story

There are so many currency items listed on eBay at any given time that it would require a Herculean effort to see everything available. However, sometimes serendipity tips in your favor.

Greetings, friends! I know that by the time you read this, the election will be over, and we will finally know the outcome of what was clearly one of the most divisive political displays in the nation’s history. I, for one, am glad not to have to listen to any more political ads or receive any more of the myriad campaign texts that have pestered me for the past few months.

This month, we will veer away from my normal national bank focus to examine an interesting piece of United States currency that I recently obtained and the neat story behind it. I am sure you will find this to be most worthwhile.

Many of you probably peruse eBay from time to time, looking for items, perhaps national bank notes, to add to your collection. There are so many items of currency listed on eBay at any given time that it would require a Herculean effort to see everything that is available. So, it is just by serendipity that I came across the note that I’m introducing to you today.

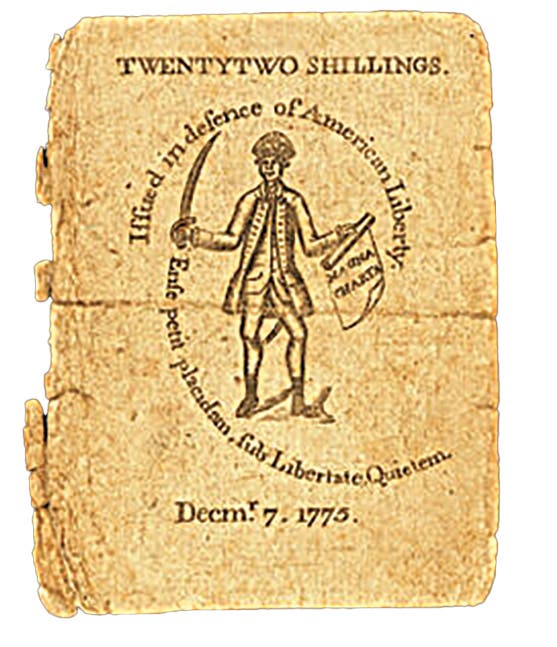

Several months back, I was listing for sale a circulated Series of 1891 $1 Treasury Note on eBay. That in itself was of no consequence. When I checked out the listing, eBay, as usual, had included a group of “similar items,” which they do (and I do not like) on new listings. The first item was a similar Series of 1891 $1 Treasury note, and it caught my eye because I could see that it had a pen inscription in red ink on the note. As many of you know, I like inscribed currency with historical references (many of you probably recall my series on Civil War inscribed currency in past issues of Bank Note Reporter.) So, I checked out that listing to read the inscription.

The note was housed in a PMG Very Fine 25 holder with a notation of “contemporary inscription.” The seller did not attempt to decipher the inscription and did not even mention it in his item description. Nonetheless, he had priced the note as if there was no writing on it. After all these years, I have gotten pretty good at reading all kinds of early cursive/script writing, and this was no exception. What I read was interesting, so I contacted the seller, got a better price, and bought the note.

Take a look at the photos accompanying this article to see the note in question. The red pen inscription reads as follows:

"Rec’d from Mrs. Geo. M. Studebaker May 15-1898 and followed the route of the 157th Ind. U.S.V. and returned to its former owner on Feb. 22, 1899."

It is worth noting that the writer had attempted to start the inscription directly under the word UNITED and above Will Pay on the note but realized he did not have enough room.

A quick Google search on the 157th Indiana U.S. Volunteers immediately located information on the unit. Lo and behold, its commanding officer was none other than Colonel George M. Studebaker. Does the surname ring a bell to you? Well, sure enough, George was a scion of the famous Studebaker auto manufacturing clan, the son of its founder.

So, what happened here was that George’s wife, having no idea what role the 157th Indiana U.S. Volunteer Infantry Regiment would play in the Spanish-American War, gave the $1 Treasury Note to her husband for good luck, with the intention he would bring it home and return it to her at the end of the conflict. That is exactly what happened: George Studebaker carried the note with him during his time with the regiment, inscribed it, and returned it to his wife on Feb. 22, 1899. Let’s get into the story of George M. Studebaker and the 157th Indiana Volunteer Regiment.

George Milburn Studebaker was born on Dec. 3, 1865, in South Bend, Ind., the eldest son of Clement and Anna (Milburn) Studebaker. Clement Studebaker was one of five brothers who founded the Studebaker Brothers Manufacturing Company. The firm was originally a coachbuilder, manufacturing wagons, buggies, carriages, and harnesses. Studebaker entered the automotive business in 1902 with electric vehicles and in 1904 with gasoline vehicles, all sold under the name “Studebaker Automobile Company.” The first gasoline automobiles manufactured by Studebaker were marketed in August 1912. Over the next 50 years, the company established a reputation for quality, durability, and reliability.

George M. Studebaker attended the Pennsylvania Military Academy in West Chester, Pennsylvania (now Widener College). Upon graduation in 1884, he married Ada Mar Lantz, the eldest daughter of Mr. and Mrs. William C. Lantz of South Bend. “The most unique and, at the same time, one of the most brilliant weddings ever celebrated in this city,” began the Sept. 4, 1885, South Bend Register’s article covering the nuptials. The grand wedding took place at South Bend’s First Presbyterian Church. The groom and groomsmen, all graduates of the Pennsylvania Military Academy, were attired in gray dress uniforms with swords and helmets with plumes. The bride wore a silk dress with a pearl-beaded front and carried white rosebuds. The reception took place at the Lantz home, which was located on the current site of South Bend’s Central High School.

George M. Studebaker went to work for the family business and later served as commanding officer of the 157th Indiana Volunteer Infantry Regiment during the Spanish-American War at the rank of colonel. He was henceforth known as Col. Studebaker. The 157th Indiana Volunteer Infantry, formed around the Third Indiana National Guard, was mustered into service at Indianapolis, Ind., on May 10, 1898. At the time of mustering in, the unit consisted of fifty officers and 972 enlisted men. The unit had the moniker of “Studebaker’s Tigers.”

The regiment was first ordered to Camp Mount at Indianapolis, and after a brief stay, they departed for Camp Thomas on May 15. Camp Thomas was located on the grounds of the Civil War battlefield known as Chickamauga in Georgia. Again, the regiment only stayed a brief time at Camp Thomas before being ordered to Port Tampa, Fla., where it arrived on June 3. In conjunction with the First Ohio Volunteer Infantry and the Third Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, the 157th Indiana guarded the government warehouses at the docks until July 29, when they were ordered to Fernandina, also in Florida.

The war ended on August 12, with the agreement between the United States and Spain on an armistice. The regiment remained in duty at Port Tampa until August 30. The regiment departed Florida, going home to Indianapolis’ Camp Mount. The members of the regiment were furloughed from Sept. 10 until Oct. 10. The regiment was mustered out of service on Nov. 1, 1898, at Indianapolis, Ind. At the time of mustering out, the regiment consisted of fifty officers and 1,223 enlisted men. During its term of service, the regiment had two officers and sixteen enlisted men die from disease. Another enlisted man was killed in an accident, ten men were discharged on disability, and three men deserted.

Due to no fault of their own, Colonel Studebaker and the 157th Indiana Volunteers gained no glory in the Spanish-American War. Unlike Theodore Roosevelt, who paid to have his Rough Riders transported to Cuba so as to get into the fight, the 157th became superfluous in a war that ended rather quickly. The 157th was hardly a typical cross-section of the general population of that time. Of its approximately 1,100 members, 350 were high school graduates, 150 college graduates, and 12 of its officers left salaries of $150 per month or more to enlist. And, of course, the wealthiest among them was the commanding officer, Col. Studebaker. At the war’s end, he returned to work at the family company in South Bend. Almost 30 years later, he had amassed a fortune of some $3,500,000.

Col. Studebaker served as Vice President of the Studebaker Brothers Manufacturing Company until 1911 and remained a stockholder until the early 1920s. He was also a major stockholder in the South Bend Watch Company and numerous other local concerns. Col. George and Ada were the last Studebakers to occupy the family mansion, Tippecanoe Place, on West Washington Street in South Bend.

Built in 1889, it was the residence of Clement Studebaker, a co-founder of the Studebaker vehicle manufacturing firm. Studebaker lived in the house from 1889 until his 1901 death. The house was designed by Chicago architect Henry Ives Cobb, who Studebaker selected after viewing high-style houses of the period in the Chicago area. Construction of the massive 64-room mansion took three years. The house is one of the few surviving reminders of the Studebaker automotive empire, which was the only major coach manufacturing business to transition to the manufacture of automobiles successfully.

In 1973, the Richardsonian Romanesque mansion was listed on the National Register of Historic Places. It was further recognized by being designated a National Historic Landmark in 1977. It is located in South Bend’s West Washington Historic District. George and Ada Studebaker and their family were the longest residents of Tippecanoe Place. They began residing there in 1889 and remained at Tippecanoe until 1933. As of 2020, the house is the location of the Tippecanoe Place Restaurant – Studebaker Brewing Company.

Sadly, everything did not end well for George M. Studebaker, despite his wealth and position. He and his brother Clement Jr. had invested heavily in the utility empire of Chicago magnate Samuel Insull, whose holding company controlled large portions of several railroads, electric companies, and power stations. Insull was highly leveraged, with an empire of $500 million with only $27 million in equity. When the Great Depression came in 1929, Insull’s holding company collapsed, and with it, the investments of 600,000 shareholders were wiped out. George and Clement Studebaker were among them.

In November 1933, Col. Studebaker filed a petition for bankruptcy, showing liabilities of $2 million, assets of $2,000, and about $35 in cash.

When this action was taken, the Studebakers moved from their ancestral home on the knoll at Tippecanoe Place, built by his father in 1889. The house, antiques, and heirlooms of the family were left behind to help satisfy claims to creditors. George and Ada were relegated to a rented white frame house in South Bend.

George M. Studebaker died on Aug. 27, 1939, aged 73. He is buried in Riverview Cemetery in South Bend. Ada Studebaker, who died in 1954, was buried next to her husband.

All in all, a rather fascinating piece of history garnered from a simple inscription on a Series of 1891 $1 Treasury note. One of the fun aspects of currency collecting is trying to think of all the places a bank note has been. In this case, I know exactly where my note was between May 15, 1898, and Feb. 22, 1899 – in the pocket of Colonel George M. Studebaker as he traveled with the 157th Indiana Volunteer Infantry Regiment. I know that after Feb. 22, 1899, it was held by Ada Mar Studebaker and kept among her personal effects until handed down in the family, to reside in my collection eventually.

You never know what goodies are out there to be found and the stories they carry, in this case, written on them. Hope you enjoyed!

Readers may address questions or comments about this article or national bank notes in general to Mark Hotz directly by email at markbhotz@gmail.com

You may also like: