New 1862-3 $1 and $2 Legal Tender Friedberg Number Varieties

The handling of Treasury signatures on currency always presented a nuisance to all involved. The volume of Federal currency issues forced rapid innovation and those changes added interesting varieties to…

The handling of Treasury signatures on currency always presented a nuisance to all involved. The volume of Federal currency issues forced rapid innovation and those changes added interesting varieties to the demand and legal tender notes as the Federal government got into the note-issuing business during the Civil War era.

The following is a revealing verbatim transcript of an item that appeared in the July, 1875, issue of the Banker’s Magazine.

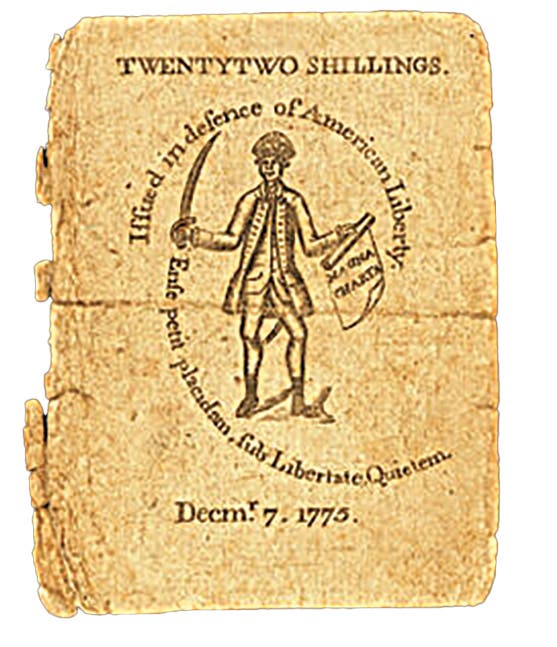

A writer in the Indianapolis Journal says: “The law requires all notes, bonds and interest coupons issued by the Government to bear the signature of the Treasurer. In former times, before the invention of greenbacks, and when the bond issues of the Government were comparatively insignificant, the Treasurer used to affix his personal signatures to them. When General Spinner came into office in 1861 he still pursued this practice for awhile, and nearly killed himself in the monotonous manual labor of writing his name. It soon became evident that the work was greater than any man could do, and left him no time whatever for other more important duties. So when the first issue of Government notes was made in the summer of 1861, a different arrangement was made. These notes were receivable for customs duties, and being payable on demand were called demand notes. The whole amount of them issued was $60,000,000. This is before the Government began to print its own notes. These demand notes were engraved and printed in New York, and sent to the Treasury Department at Washington to be signed by the Treasurer and Register. As the theory still prevailed that they must be signed by hand, a force of about eighty clerks was organized to do the work by deputy, one-half acting as Deputy Treasurers and the other as Deputy Registers. At first the words ‘for the’ had to be written in, making the signature read, ‘John Jones, for the Treasurer,’ or for the Register, as the case might be. Afterwards the words “for the” were engraved, and only the signature had to be written. The signing of the $60,000,000 of demand notes occupied this force of eighty men about six months—from August, 1861, to February, 1862. Although the Government credit was good at that time, it was even then sorely pressed for ready money to meet the heavy expenses of organizing and equipping the Army. Thus the demand notes were called for faster than they could be signed, and it often occurred that the whole force of clerks was kept at work till nearly midnight signing bills which would be cut and trimmed early the next morning, and in some paymaster’s chest before night. It happened to the writer to have charge of the work, and he well remembers the high degree of gratification evidenced by the then Secretary of the Treasury, Mr. Chase, on learning that the last sheet of demand notes had been signed without the loss of a dollar. These were the last Government notes signed by hand.

Figure 1 reveals that the deputy signers not only hand signed the notes, but due to lack of foresight, they even were required to write “for the” in front of the official’s titles.

In short order, as shown on Figure 2, the Treasury requested the bank note companies to engrave “for the” onto the plates, which virtually halved the work of the deputy signers.

After the last of the demand notes were finished in early 1862, and the legal tender notes were on their way, the officials in the Treasury Department sprang for a major innovation for handling the Treasury signatures. They ordered the bank note companies to overprint facsimiles of the actual Treasury official’s signatures on the legal tenders. See Figure 3.

Simultaneously, they also decided to have Treasury seals printed on the notes wherein the seals became the monetizing instrument that turned the notes into money rather than the signatures of the Treasury officials. Thus, the American Bank Note Company was commissioned to design and produce seals, which were purchased by the nascent Bureau of Engraving and Printing.

The bank note companies provided uncut sheets complete with Treasury signatures to the Treasury, and the seals were overprint in the Treasury as a security safeguard. Then the Treasury cut the notes from the sheets.

In due course, as the 1862-3 legal tender series wore on, another bright light went off. Treasury had the bank note companies roll engraved facsimiles of the Treasury signatures onto the plates, which saved one printing step. See Figure 4.

The engraved signatures are readily distinguished from the overprinted signatures in a number of ways. Most significant is that there are minor stylistic differences in the shapes of the punctuation marks within Spinner’s signature and the shapes of various loops in both signatures. Chittenden’s engraved signature exhibits a noticeably finer line weight than the overprinted signatures. Many of the overprinted signatures appear a bit bolder and sometimes the tighter loops in Chittenden’s signature are partially filled whereas the engraved signatures are more crisply formed.

The overprinted signatures wander quite a bit in the spaces provided for them when several of the notes are compared whereas the engraved signatures generally occupy fairly fixed positions. However, there is minor wandering of the engraved signatures as well, a finding that demonstrates that the signatures were added to the plates as a separated roll transfer after the generic face images had been laid in rather than being engraved on the master die. The engraved signatures simply wander much less than the overprinted signatures.

The job of distinguishing between overprinted and engraved signatures is most difficult on the $1 and $2 1862-3 legal tender notes because the signatures are obscured by the green tint that underlies them. Consequently, the varieties were not recognized. The result is that separate Friedberg numbers were not assigned to the $1s and $2s whereas they were for the other denominations. Both were lumped under the $1 Fr.16b and $2 Fr.41 labels.

The newly identified $1 and $2 1862-3 legal tenders with overprinted signatures constitute new Friedberg numbers. Fr.16b and Fr.41 will continue to represent the common engraved variety, and likely new numbers $1 Fr.16d and $2 Fr.41e will be attached to the scarcer overprinted varieties.

The series number printed on the notes will help greatly to distinguish between the overprinted and engraved varieties. The overprinted $1s are Series 166-170 and $2s series are 88-101 whereas the engraved $1s are 170-174 and $2s 101-171. Only $1 series 170 and $2 101 will require careful analysis because the engraved signatures were added to those plates mid-series.

All of you who collect, deal in or grade those notes know that the 1862-3 legal tenders are a genuine pain to classify by correct Friedberg number. Murray and I published a chart in the January-February 2019 issue of Paper Money designed to take the ambiguity out of making those assignments. We have expanded that chart to include the new $1 and $2 overprint entries as well as to update some of the data for the other varieties.

I’ll be glad to send you a digital copy of the new chart in the form of an EXCEL spreadsheet if you will send me a request for it with your email address. peterhuntoon@outlook.com.

All photos shown here are courtesy of the Heritage Auction Archives

Sources

Banker’s Magazine, July, 1875, Mr. Spinner’s signature: Third Series, vol. x, no. 1, p. 68.

Edmunds, George F., Mar. 3, 1869, United States Securities: Joint Select Committee on Retrenchment, 40th Congress, 3rd Session, Senate Committee Report 273, Government Printing Office, Washington, DC, 436 p.