Rondout, N.Y. Bank Issued Fascinating Varieties in all Series

The First National Bank of Rondout, N.Y. is one of the most fascinating national banks I have encountered in all my years of analyzing national bank notes. I like technical…

The First National Bank of Rondout, N.Y. is one of the most fascinating national banks I have encountered in all my years of analyzing national bank notes. I like technical issues that caused varieties on notes and it doesn’t get better than with this bank.

Just about everything peculiar that could happen, happened!

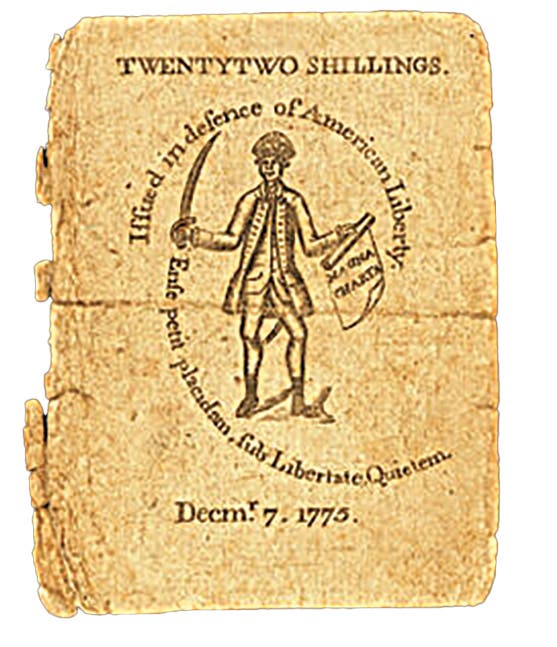

The bank was chartered in 1863 with charter number 34. It was organized under the Act of Feb. 25, 1863, wherein the bankers got to select the length of their corporate life. The bank was forced to liquidate and reorganize in 1880 under charter 2493 because the bankers had chosen a corporate life of less than 20 years and their clock was running out.

The Comptroller, in the interests of economy, had the BEP reuse the old plates for the new bank, something that happened for only a handful of banks across the country. The result was a trove of $5 Original/1875 plate varieties.

By the time the bank was reorganized in 1880, the town Rondout had been annexed to Kingston, so the town wasn’t right on the old plates. This situation festered for 40 years to the end of the Series of 1882. Finally, the Comptroller imposed a town name change on the bank by adding Kingston to their existing title. This yielded “The First National Bank of Rondout, Kingston,” which showed up on the Series of 1902 and 1929 notes. Kingston appears inconspicuously in the postal location on the 1902 notes, whereas is screams for attention on the 1929 notes.

The most interesting plate varieties were the $5 Original/1875s. They sported various act approval dates, two plate dates, three different Treasury signatures pairs, and, for the true die-hards, different face vignette varieties.

A national bank is a legal entity that conducts its business at a specific location—or locations if permitted by state law. It operates under a franchise granted by the Comptroller of the Currency as authorized by Congress. As such, it has a title approved by the Comptroller of the Currency.

The formal—legal—definition of a bank title as used by the Comptroller of the Currency during the note-issuing era was: the name of the bank including the name of town, but not that of the state.

Bankers filed an organization certificate with the Comptroller of the Currency’s office when they applied to establish a national bank. The most recent form for organization certificates used by note-issuing banks contained the following language:

First. The title of the association shall be “______________________________.”

Second. The said association shall be located in the ___________ of __________, county of __________ and State of __________, where its operations of discount and deposit are to be carried on.

The title of the bank was to be placed inside the quotes printed on the form. The first blank under Second described the legal standing of the town under applicable state law; that is, the word “city,” “town,” “village,” “borough,” etc., was to be inserted. This was followed by the name of the town in the next blank.

This form morphed slightly over time, but always was imperfect because there was ambiguity about how it should be filled out. Many applicants did not understand that they were to incorporate the name of their town inside the quotes in the blank for the bank title because there was a second blank that also called for the town. Consequently, many applicants omitted the town thus producing an incomplete title. Others incorporated a location within the quotes that was somehow deficient.

When the Comptroller’s office received an organization certificate, the banker’s title was passively accepted as was even though it didn’t meet the definition of a title because the town was missing or deficient. Instead of bouncing it back to the organizers with a request for repairs, the faulty title was treated as sacrosanct.

The protocol was to place the title exactly as received inside the quotes from the bankers, including all punctuation, above the will-pay line within the title blocks regardless of completeness, grammatical syntax or how awkward it sounded.

A space was reserved on the left side of title blocks opposite the plate date that generally was used to specify the postal location of the bank. That name was written rather inconspicuously in script. In most cases, the name of the town was repeated both in the title and in the postal location.

However, in cases where (1) the town was omitted or (2) the name submitted was deemed to be deficient, the Comptroller’s clerks would place the town or the corrected town name in the postal location. Thus, the title submitted by the bankers on display above the will-pay line coupled with the town inserted in the postal location by the clerks served to satisfy the Comptroller’s definition of a bank title. The sole objective of this machination was to provide sufficient information on the note to allow a note holder to find the bank in order to redeem the note for lawful money

One of the most interesting examples of a Comptroller-imposed town name change resulting from an annexation involved The First National Bank of Rondout, N.Y. (2493). This situation requires a bit of background.

The First National Bank of Rondout was chartered in 1863, under charter 34, in the village of Rondout. Rondout was a bustling port that straddled Rondout Creek just upstream from where it flows from the southwest into the Hudson River. The village had been incorporated in 1849. The strategic importance of Rondout was that it was the major port on the Hudson River at the eastern terminus of the 108-mile-long Delaware and Hudson Canal built in the late 1820s to transport coal from the vicinity of Honesdale, Pa., in the Delaware River Basin. The town was in a narrow valley with the village of Kingston on the higher ground to the northwest.

There was uncertainty in the early 1880s about passage of an act that would allow for a corporate extension, so bank officers facing expiration began to get nervous. They could gamble on possible extinction of their bank as they sat around awaiting legislation that would allow for extensions, or they could preemptively liquidate their bank and reorganize it as a new bank. The officers of 75 banks decided to liquidate and reorganize. The first of these was The First National Bank of Rondout because the bankers had chosen a corporate life of less than 20 years so liquidation was eminent in 1880.

The First National Bank of Rondout (34), was liquidated Oct. 30, 1880, and a new bank with the same title and officers was organized October 15 to replace it. The successor received charter 2493 on Oct. 18, 1880.

However, the villages of Rondout and Kingston had merged to form the city of Kingston eight years before in 1872. This is the joker in this tale.

The organization report for the new bank reveals that the bank title submitted by the bankers remained “The First National Bank of Rondout.” The bankers or their lawyer omitted Kingston from inside the quotes on their organization certificate. However, Kingston was correctly inserted in the blank calling again for the town. The clerks in the Comptroller’s office failed to acknowledge Kingston as either the town or post office at the time the bank was chartered or in subsequent paperwork.

In fact, as an expedient, the Comptroller directed the Bureau of Engraving and Printing to alter the existing Series of 1875 plates previously used for charter 34 for use by the new bank. This was done by leaving the title as The First National Bank of Rondout and the postal location written in script as Rondout, but updating the plate date and Treasury signatures. Consequently, Kingston was missing from all the Series of 1875 plates and subsequent 1882 plates used to print notes for the new bank. See Figure 1.

The Comptroller’s clerks finally noted on their ledgers that the post office was Kingston when the bank was extended for a second time in 1920. They ordered the Series of 1902 plates to read The First National Bank of Rondout, with Kingston in script. This constituted an informal Comptroller-imposed town name change wherein the title technically became “The First National Bank of Rondout, Kingston.” Rondout was in effect relegated to district status within Kingston, probably as the bankers had intended in 1880.

When the Series of 1929 notes were printed, the Comptroller’s clerks ordered them to read The First National Bank of Rondout, Kingston. Thus, the Comptroller-imposed town name change was in prominent display on the small size notes.

This is a case involving a Comptroller-imposed town name change that was not caused by bankers trying to avoid the costs of new plates, at least not for charter 2493. Rather, it was a belated attempt on the part of the Comptroller’s office to correct an improperly filled out organization certificate submitted by the bankers back in 1880.

The Comptroller’s decision to recycle the existing plates for charter 34 in 1880 was not appropriate for charter 2493, because the language on the plates did not acknowledge that Kingston was where the bank was located. Consequently, the Comptroller’s office was culpable in this chain of events.

The $5 Original/1875 series plates used by the two banks have one of the most convoluted histories involving national bank notes.

Four different Series of 1875 plate combinations were used by charter 34; specifically, 1-1-1-2, 5-5-5-5, 10-10-10-10 and 20-20-20-50. All but the 1-1-1-2 were altered for use by 2493. This was accomplished by updating the plate dates to November 2, 1880, and changing the Treasury signatures to Schofield-Gilfillan.

The $5 A-B-C-D plate for 34 was a Continental Bank Note Company Original Series plate that carried an 1863 act approval date and Chittenden-Spinner Treasury signatures. The act approval date remained unchanged when the plate was altered by the BEP into a Series of 1875 form, but the Treasury signatures were updated to Allison-New, both of which were appropriate.

When the plate was altered for use by charter 2493—a bank organized under the Act of 1864—the now obsolete 1863 act approval date was grandfathered in the lower margin. The plate date was changed to November 2, 1880, and the Treasury signatures were updated to Schofield-Gilfillan. The plate still carried the original variety 2 vignettes. Thus, it carried the wrong act approval date and vignettes that greatly predated the variety 4 vignettes in use in 1880!

Eventually two $5 Series of 1875 duplicate plates were made for 2493, respectively lettered E-F-G-H and I-J-K-L. They were made with an 1864 act approval date and contemporary variety 4 vignettes. All totaled there were three different configurations for the first plate. The two duplicates represented a fourth configuration. What more could a technophile ask for? Pulling together a set of notes from them would be a considerable challenge.

Just a quick note about the vignettes on the faces of $5 Original/1875 notes. Four pairs of distinctly different vignettes were used on those notes. They have been described in the literature in great detail. Suffice it to say that you can readily see an obvious difference between the right vignettes on Figures 4 and 5 by comparing the shapes of the top of the tree to the left of the 5 in the upper right corner. Of course, there are numerous other differences.

Source for Photos

Bureau of Engraving and Printing, 1875-1929, Certified proofs lifted from national bank note face plates: National Numismatic Collections, Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.; Both Series of 1929 notes. Pete Papadeas.