Sleeper Territorials

This is the story of three sleeper territorial issues. I define territorial sleepers as large size territorial notes that don’t carry the Territory label in their title blocks—not Territory, Terr,…

This is the story of three sleeper territorial issues.

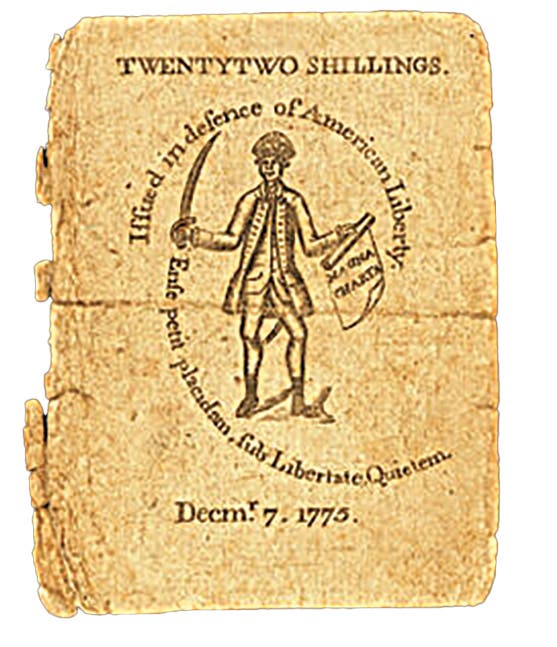

I define territorial sleepers as large size territorial notes that don’t carry the Territory label in their title blocks—not Territory, Terr, Ter or even T—yet are genuine territorial issues from plates made during the territorial era that carry a territorial plate date.

The notes carry territorial plate dates; thus, the sleeper aspect is that you must carefully read the plate date to recognize that they are indeed territorial notes. See Table 1. The unwary miss them.

Notice that there happened to be one from each major large-size series. Each has a story to tell.

The preparation of this article was stimulated by the recent appearance of the spectacular $10 brown back from The State National Bank of Oklahoma City pictured here as Figure 1. It was misattributed by PMG as a state note.

The three sleeper plates will be profiled beginning with the Nebraska City Original/1875 plate.

Apparently, the word Territory was simply omitted from the plate order for the 10-10-10-20 Original Series plate for The Otoe County National Bank of Nebraska City because it wasn’t included in the title blocks when the plate was made by the American Bank Note Company in 1865. See Figure 2. In contrast Territory was included on the 5-5-5-5 plate made by the Continental Bank Note Company for the bank at about the same time and later on the 1-1-1-2 plate made from a $1 American Bank Note Company die and $2 Columbian Bank Note Company die.

Nebraska was admitted as a state on March 1, 1867, but back then they didn’t alter the plates to reflect the change. In time, all three of the Nebraska City plates were altered into their Series of 1875 form after the plates were turned over to the Bureau of Engraving and Printing. However, the title blocks were left as was except for updating the Treasury signatures from Colby-Spinner to Allison-New.

The three plates continued to be used as needed until the bank was extended in 1885. The 10-10-10-20 without a territory label carried the territorial plate date of Sept. 1, 1865, right to the end. Because of that, all the notes printed from the plate are numismatically classified as territorials, even though most were printed and issued after statehood. This case is particularly ironic because even the Series of 1875 used for the last of them postdated Nebraska as a territory.

The Series of 1902 10-10-10-20 plate for The First National Bank of Juneau made in 1918 was ordered without a territory label as well. The status of Alaska was changed from district to territory on August 12, 1912. The ordering clerk in the Comptroller’s office just wasn’t paying attention to such distinctions at that late date. See Figure 3.

The most interesting case involved the Series of 1882 10-10-10-20 plate for The State National Bank of Oklahoma City. That bank was organized in 1893, 14 years before statehood. Clearly the bankers were serious promoters of statehood so used their bank name to that effect. Apparently, the ordering clerk found it inconsistent to use Territory in the title block for a “State National Bank”, so he omitted it from the plate order form, despite the fact that the duplicate organization report of the bank in the National Archives reveals that the bankers used Territory of Oklahoma on their organization certificate. All the other Oklahoma territorial banks received notes with territory labels.

Curiously, the officers in six younger territorial banks also used the State National title, including three in Oklahoma Territory, yet all received notes with territorial labels. See Table 2 and Figure 4.

The siderographers at the Bureau of Engraving and Printing altered all the active Indian and Oklahoma territorial plates after Oklahoma was admitted to reflect their new statehood status. The plate dates on them were revised to Nov. 16, 1907, which was statehood day, and the Treasury signatures were updated to Vernon-Treat, who were in office on Nov. 16, 1907, to match. The proof illustrated on Figure 5 is from the state version of the State National plate, from which 1,500 sheets of brown backs were printed.

Pairing a territorial and state brown back note from the plate would be a feat! None of the state brown backs have been reported in the National Currency Foundation census. There are four reported 1882 date backs from the 10-10-10-20 combination though.

Of the three plates treated here, the Oklahoma City plate was the only one to be altered into a state form. The changeover printings between the territory and state printings are listed on Table 3. All the territorial notes were printed during the territorial period, although the last of them continued to be sent to the bank until the supply was exhausted. Notice that the note illustrated in Figure 1 is from the last territorial printing.

Territory labels were omitted from the Series of 1929 overprinting plates for the Alaska and Hawaii issuers, which were the only remaining territorial national banks when the small size notes came along. Alaska was admitted as a state on Jan. 3, 1959, and Hawaii on Aug. 21, 1959.

The note illustrated on Figure 1 brought the census of reported territorial brown backs for The State National Bank of Oklahoma City to five. The bold penned signatures of president Edward Howd Cooke and cashier James Louis Wilkin give it terrific eye appeal.

Cooke was born in Brenham, Texas in 1858. He served as cashier at The Colorado National Bank, Texas, charter 2801, between 1890 and 1892, prior to coming to Oklahoma City. Once he helped organize The State National in Oklahoma City, he served as cashier from 1893 to 1899, president 1900 to 1918, and chairman of the board 1919 to 1927. He died in 1939 in Los Angeles, Calif.

Cashier Wilkin was born in Athens, Ohio in 1859. He served in the State National from its founding, becoming assistant cashier 1895-1897, cashier 1900-1908, and vice president 1909-1911. He left to purchase the Night and Day bank in Oklahoma City in 1911 with John M. Hale, which they renamed the Wilkin-Hale State Bank in Oklahoma City. That bank failed during the post-World War I agricultural depression in 1921. The failure took a serious toll on Wilkin’s health, from which he didn’t recover. He died in 1923. He was a highly regarded civic-minded individual who was a director of the state fair association and became its president in 1914. He also served on the board of regents of the University of Oklahoma.

As time marched on, the officers of The State National bought out a number of competing Oklahoma City banks and took on new names after the most important of those acquisitions, ultimately becoming the largest Oklahoma bank during the note-issuing era. It became First National Bank in Oklahoma City in 1919, laying claim to the First National title having absorbed The First National Bank, charter 4402, back in 1897. They issued only $50 and $100 1902 plain backs with the First National title.

Upon merging with The American National, charter 5716, in 1927, the bank became The American-First National Bank but never issued notes with that title. Cooke left the bank during the merger. The reason no notes were issued with the American-First title was that the bankers had sold all their bonds used to secure circulation in 1925 and didn’t buy back in until 1932 during the small note era.

The bank took on trust powers in 1930, becoming The First National Bank and Trust Company of Oklahoma City. The 1929 issues, all with that title, comprise the most common of the Oklahoma 1929 issues.

The State National Bank was a very interesting bank that certainly got off on the right numismatic foot with their sleeper brown bank $10 and $20 territorial oddities.

The data pertaining to Cooke, Wilkin and the bank came from the Society of Paper Money Collectors Bank Note History Project website.