Ten-Month Circulation of Santa Fe Series of 1929 Notes

The entire Series of 1929 issuance from The First National Bank of Santa Fe, N.M., amounting to a circulation of $150,000, occurred in just 10 months between March 23, 1933, and Jan. 19, 1934.

The entire Series of 1929 issuance from The First National Bank of Santa Fe, N.M., which amounted to a circulation of $150,000, occurred in just 10 months between March 23, 1933, and Jan. 19, 1934. The purpose of this article is to explain what took place from the perspective of the records available to us in the Annual Reports of the Comptroller of the Currency and the National Currency and Bond Ledgers in the National Archives.

Bank president Arthur Seligman was an astute businessman who was working to optimize the profitability of the bank as they were attempting to recover from the depths of the Great Depression. His actions recounted here opportunistically took advantage of a short-term bond play that materialized through the passage of the Federal Home Loan Bank Act of 1932. He used the liquid assets of the bank to purchase high-yield government bonds that temporarily were accorded circulation in order to maximize the profitability of the bank while minimizing the risks of the times.

Arthur Seligman (1871-1933)

The following is from Golden and Rywell (1950, p. 231).

Seligman was a businessman and politician who was born in Santa Fe, New Mexico Territory, on June 14, 1871. In 1887, he graduated from the Swarthmore College preparatory school in Pennsylvania and, in 1889, from Union Business College in Philadelphia. He then engaged in the family businesses in Santa Fe, rising to become president of the Seligman Brothers mercantile firm (1903–1926), president of the La Fonda Building Corporation (1920–1926), and auditor and board member of the Northern New Mexico Loan Association.

He was a Democrat who was seriously involved in New Mexico politics throughout his life. His party leadership positions included chairman of the Santa Fe Democratic County Central Committee (1895–1911), chairman of the territorial Democratic Committee (1895–1911), chairman of the state Democratic Committee (1912–1922), and delegate to the Democratic National Committee (1920–1933). He served as a member of the state Irrigation Commission (1904–1906), a member of the New Mexico Board of Equalization (1906–1908), chairman of the Santa Fe County Commission (1910–1920), and president of the state Educational Survey Commission (1921–1923).

Seligman was elected mayor of Santa Fe (1910–1912) and two-term governor of New Mexico in 1930 and 1932. He served as governor from January 1, 1931, until his death on September 25, 1933.

He assumed the presidency of The First National Bank of Santa Fe in late 1924 and served in that capacity until his death.

Seligman and Circulation

By the time Seligman took over as bank president, the former officers had built the circulation of the bank up to $150,000 from $45,000 in 1919, as illustrated in Figure 3. They secured this circulation with 2 percent Consols of 1930. It is obvious that Seligman thought there were better opportunities than that investment and the money that could be earned on loaning the attendant circulation. The bonds were sold on Dec. 11, 1924, and the bank got out of the currency-issuing business. From then on forward, the liability for the bank’s outstanding large-size notes was assumed by the Treasury, and those notes were actively redeemed from circulation.

It is clear from the table below that the bank continued to prosper until the onset of the Great Depression. A contraction in total resources ensued through 1932. During this stressful period, Seligman was managing the bank very conservatively and increasing its cash reserves.

Federal Home Loan Bank Act of 1932

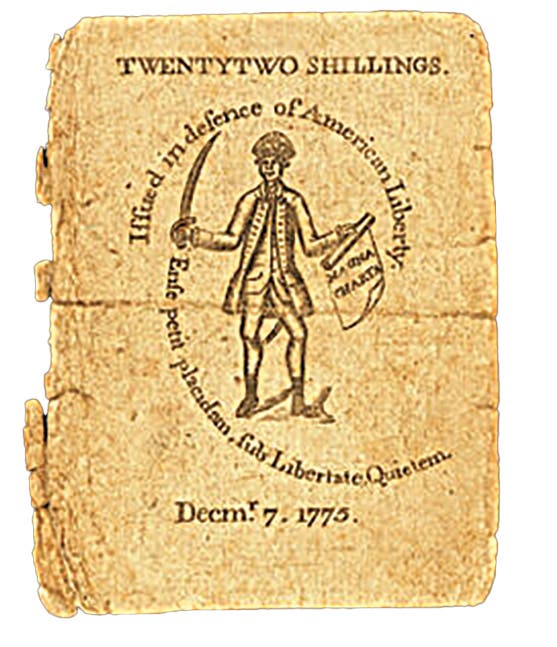

In 1932, a Hoover-era economic stimulus act was passed called the Federal Home Loan Bank Act. Its objective was to lower the cost of home ownership by creating a network of government banks to provide low-cost home mortgages. The bill was signed into law by President Herbert Hoover on July 22, 1932.

However, the form in which it passed was a notable dud because the only people who could qualify for the mortgages were sufficiently well off. They didn’t need to fool with the Federal Home Loan Banks (Wikipedia).

Here is where it gets interesting. Over the objections of Hoover and his Treasury officials, a rider was tacked onto the bill known as the Glass-Borah Amendment. The amendment provided for a three-year circulation privilege for all U.S. bonds that paid interest of 3-3/8 percent or less from the date of passage of the act. The rider had nothing to do with the Federal Home Loan Banks.

Its sponsors were Virginia Democratic Senator Carter Glass, former Secretary of the Treasury under Woodrow Wilson, and Idaho Republican Senator William Borah. Both were progressives. Clearly, their amendment was a clumsy attempt to inflate the money supply during the Great Depression because it would make national bank note circulation sufficiently profitable that it would incentivize bankers to invest in the higher-yield bonds and take out additional circulation.

Use of the high-interest bonds to secure national bank notes would terminate on July 22, 1935, under the terms of the amendment.

Seligman Reacts

It is clear that Seligman saw this as a good short-term opportunity to buy into risk-free Treasury bonds that paid what looked like a good return at the depths of the depression. On March 21, 1933, his bank bought $150,000 worth of Treasury 3 percent Bonds of 1951-55 to secure new currency issues.

The notes the bank received were printed from a set of six 1-subject Barnhart Brothers & Spindler logotype plates made during March 1933. Remarkably, the printing of type 1 notes arrived from the Bureau of Engraving and Printing two days after the bonds were recorded in the National Currency and Bond Ledgers as being deposited with the U.S. Treasurer. $150,000 worth of nationals was shipped to the bank that same day. It usually took about two weeks for such plates to arrive from the contractor so it is evident that either the Comptroller had advanced knowledge of the bond deposit or the date associated with it in the ledger post-dated when the bonds were actually deposited with the Treasurer.

The bankers quickly began to circulate the notes because the first of them began coming in for redemption on June 13, 1933.

Arthur Seligman died Sept. 25, 1933.

Bond Sale

The new president, P. A. Walter, didn’t wait until July 22, 1935, to sell the bond position —the date when the temporary circulation privilege expired. Instead, the bonds were sold at the beginning of June 1934, so the bank was once again out of the currency-issuing business. By then, its total resources had rebounded and were rising as if the Great Depression hadn’t occurred. Obviously, Seligman’s short-term position in the bonds proved wise, but now the bankers had better opportunities for that money than government bonds and the profits that could be made from issuing national currency against them.

In the meantime, the replacement of worn Series of 1929 notes depleted the initial printing of type 1 notes, so a second printing was received by the Comptroller’s office on Oct. 6, 1933. However, it consisted of type 2 notes. Thus, the bank got to issue both types during the short time that it was using the series.

Consequences

The reports of condition for national banks published in the annual reports of the Comptroller of the Currency dating from 1926 forward were called on December 31st. The deposit of the bonds to secure the Series of 1929 issues by The First National Bank of Santa Fe spanned March 21, 1933, to July 2, 1934, so the bankers were liable for the circulation tax only for that period. Consequently, their $150,000 worth of Series of 1929 notes appeared only in their 1933 report of condition, yielding the one-year spike in Figure 3. It was this unusual one-year spike that caught our attention.

We collectors tend to view the issuance of national bank notes as a continuum. Cases such as this are jarring and always worth exploring because they involve unusual circumstances. Once we discovered it, we took a look at the bank’s Series of 1902 plain back issues knowing they were equally unusual because they terminated at the end of 1924. Sure enough, the high serials reported from that series in the National Currency Foundation census are the following: $5 N18313H-11552-F and $10 R614784H-7882-C, both printed in 1924. Had the bankers not sold their bonds in 1924 but instead continued issuing until the end of the large note era in 1929, their Series of 1902 notes would have been far more common than they are.

References Cited

Congressional Record, Senate, 72nd Congress, First Session, July 8, 1932, p. 14853 & July 11, 1932, p. 15004.

Golden, Harry, and Marin Rywell, 1950, Jews in American History, their contributions to the United States of America: H.L. Martin Company, Bayonne, NY, 489 p.

Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Federal_Home_Loan_Bank_Act.