Unusual Civil War vintage notes

By Mark Hotz Last month, I brought to you a very interesting American short snorter of World War II vintage, this one belonging to none other than John A. Roosevelt,…

By Mark Hotz

Last month, I brought to you a very interesting American short snorter of World War II vintage, this one belonging to none other than John A. Roosevelt, youngest son of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who served as a naval officer in the Pacific toward the end of the war. This month we will look at the Civil War.

Inscribed currency from the Civil War is rather hard to find, notwithstanding the occasional Confederate piece with someone’s attempted forgery of Robert E. Lee’s signature scrawled upon it. I have in my collection several unusual items of Civil War vintage. The first that I will present to you is a $1 bank note of the Girard Bank of Philadelphia, dated Jan. 9, 1862. Inscribed in bold pen on the back is the following:

“This Note was given / to Mrs. Celia Coe / By J. G. Stewart of / the Mobile Cadets/ He took it out of / a Federal Cols. / Pocket on the Battle / field of the Seven / Pines the first Battle / he was ever in / given to her at / Winchester Virginia / October 21st 1862.”

I am sure many of you can see how this item certainly piqued my interest, and my excitement was palpable when I obtained it. I initiated an Internet search in an effort to find out more about J.G. Stewart and the mysterious Mobile Cadets. After a short but determined inquiry, I found some information that really brought the item to life.

The Mobile Cadets were none other than Company A, 3rd Alabama Infantry Regiment. The Mobile Cadets consisted of volunteers from Mobile County, Ala., and was the very first company to volunteer to serve the Confederacy. The 3rd Alabama was the first regiment from that state to offer its services to the Confederate cause and the first to be sent to Virginia for mustering duties. Jones M. Withers was elected its first colonel.

The 3rd Alabama had been held in reserve in Norfolk for almost a year without seeing any action. Its “baptism of fire” came on June 1, 1862, at the battle known as Seven Pines to the Confederates and Fair Oaks to the Federals. This battle was part of the great Peninsula Campaign in which the Union Army, under the command of Gen. George McClellan, came within 10 miles of Richmond but failed to capture it.

The 3rd Alabama, with the Mobile Cadets as Company A, was held in reserve the first day of the of the battle (May 31, 1862), but was thrown into the fight and badly cut up on June 1, losing 38 killed in action and 122 wounded. Two weeks later, the regiment was made part of General Daniel Hills’ Division and took part in battles before Richmond. When the Confederates advanced across the Potomac in September, the 3rd Alabama was the first Confederate regiment to plant the Stars and Bars flag in Maryland. It was engaged in heavy fighting at Boonsboro and Antietam before retreating with the rest of the army into the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia.

On one website, I was able to find a roster roll of the 3rd Alabama Infantry Regiment. All of the men were listed alphabetically, with their company and rank. Eagerly and with anticipation, I scrolled down to “S.” Stewart had been in Company A, the Mobile Cadets. He had enlisted as a private and ended his service as a sergeant. There was no indication of whether he had been wounded or killed.

It was very exciting to be able to make this currency-related relic come alive. At least now I knew something about Pvt. Stewart and his unit. I do not know his relationship to Mrs. Celia Coe, but I can surmise from the date inscribed that the regiment had been regrouping in Winchester after the Battle of Antietam. Perhaps Stewart had been billeted in Mrs. Coe’s home?

I have yet to determine the identity of the officer from whose pocket the note was taken, but how many colonels of Philadelphia units could have fallen at Seven Pines? If any readers can offer any further assistance here, I would be grateful.

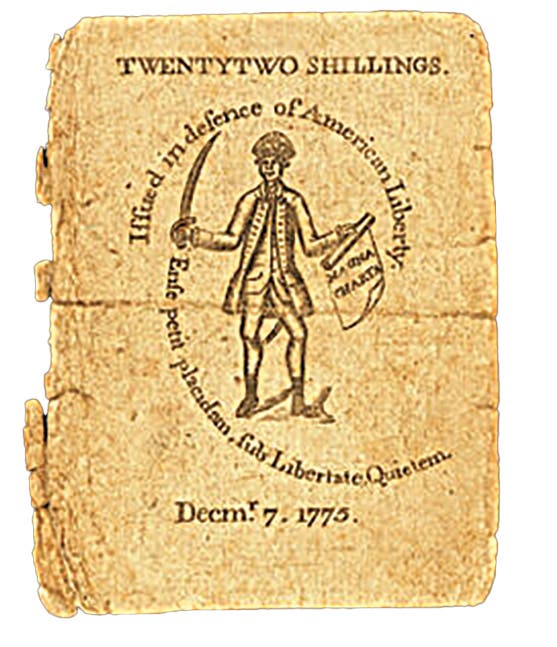

The next item I’ll present to you I was very fortunate to find just in the last month. While visiting an out-of-state coin shop, I came across a Corporation of Winchester, Virginia, 10-cent note issued Oct. 4, 1861. This in itself is not a rare note and can generally be found on the market for a very reasonable price. However, when I turned it over, I found a most interesting pen inscription, which resulted in my adding this note to my collection. It read as follows:

“This was found upon the person of Col. Baldwin, on his being made prisoner at Blooming Gap.”

Above the ink inscription, in a far less sophisticated hand, and in pencil, was scrawled “Col. Baldwin Blooming Gap.” This looked all very intriguing to me, and though I had never heard of Blooming Gap, I thought it was worth researching.

Here is what I learned. It turned out that what the Federals called Blooming Gap was actually known as Bloomery Gap, and a battle took place there on Feb. 14, 1862. Early in 1862, Confederate raids and attacks put Hampshire County, Va. (now West Virginia) and much of the surrounding area under nominal Southern control. The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad and nearby telegraph wires were severed, impeding Federal troop movements.

A militia brigade under Col. Jacob Sencendiver, 67th Virginia Militia, occupied Bloomery Gap to threaten the railroad and Union-occupied territory near the Potomac River. To drive them out, Union Gen. Frederick W. Lander led a mixed force of infantry and cavalry south from Paw Paw, Morgan County, on the afternoon of Feb. 13. He intended to strike Sencendiver’s position at dawn the next morning, but bad weather and high water delayed him long enough for the Confederate pickets to give warning.

Sencendiver hastily ordered the wagons packed and sent east while posting the 31st Virginia Infantry to block Lander’s advance. Lander led the charge of part of the 1st West Virginia Cavalry (Union), overrunning and scattering the Virginians and capturing many officers and men, as well as the wagon train. Sencendiver rallied the 67th and 78th Regiments, however, and recaptured the wagons. The Federals returned to Paw Paw while the Confederates marched to Pughtown, leaving the railroad and telegraph lines open for the day. Sencendiver soon reoccupied the gap.

The battle routed the Confederates, who lost 13 killed and 65 captured. Among the officers captured was none other than Col. Robert F. Baldwin, commander of the 31st Virginia Infantry regiment. Baldwin and his staff were surprised by the Federal cavalry, and Baldwin surrendered to Gen. Lander personally. A report submitted by Sencendiver to the Headquarters of the 16th Brigade, Virginia Militia, on Feb. 17, included a reference to Col. Baldwin:

“Our advanced pickets came in about daylight and reported the enemy advancing upon us in large force. I gave orders to have the baggage packed immediately and the men prepared to meet the enemy and repulse him if possible. The Thirty-first Regiment, Colonel Baldwin, being quartered nearer the point from where the enemy was advancing than the balance of the command, rushed hurriedly to meet him…Our loss, I regret to say, is over 50 officers and privates missing. Annexed is a list of officers captured: Col. R. F. Baldwin, Thirty-first Regiment; Capts. William Baird, acting assistant adjutant-general, and G. M. Stewart, Eighty-ninth Regiment…”

Baldwin was eventually sent as a prisoner to Fort Warren, located in Boston Harbor. On May 16, 1862, Brig. General Lorenzo Thomas, Adjutant General of the Union Army, sent the following message to Col. J. Dimmick, commander at Fort Warren: “SIR: You are authorized and directed to transfer Colonel R.F. Baldwin, Thirty-first Virginia Regiment, now in your custody, to Gen. Wool at Fortress Monroe, to be held by him for exchange of Colonel Corcoran, now a prisoner at Richmond.”

At the same time, Thomas wrote to Maj. Gen. John E. Wool, commander of Fortress Monroe to that effect, adding “…Upon his (Baldwin’s) arrival at Fortress Monroe, you will notify the rebel officer nearest to you that he is there to be exchanged for Colonel Corcoran, now a prisoner in Richmond, and upon the arrival of the latter at Fortress Monroe, you are authorized to release Colonel Baldwin.”

Col. Corcoran was the commander of the 69th New York Infantry Regiment who had been captured at First Bull Run. I have not been able to trace Baldwin after the point of his exchange, which took place in August. The 10-cent note that I acquired was obviously taken from the colonel’s possessions. The penciled inscription was probably made at the time by the soldier who was responsible for searching the colonel. Later, the pen inscription was added. But what an interesting story it is. The Battle of Bloomery Gap was a small one-day affair, and this note may well be the sole remaining souvenir of that fight.

Today, the Battle of Bloomery Gap is largely forgotten, with just a historical marker placed in front of the Bloomery Gap Presbyterian Church on West Virginia Route 127 in Bloomery, located just across the line from Virginia, about 20 miles northwest of Winchester. I have included a photo.

Readers may address questions or comments about this article to Mark Hotz directly by email at markbhotz@aol.com.

This article was originally printed in Bank Note Reporter. >> Subscribe today.

More Collecting Resources

• Order the Standard Catalog of World Paper Money, General Issues to learn about circulating paper money from 14th century China to the mid 20th century.

• Any coin collector can tell you that a close look is necessary for accurate grading. Check out this USB microscope today!