What is Federal Reserve Bank Note?

The paper money you carry around in your wallet these days has a green Treasury seal on them, which is one of the distinctive characteristics of Federal Reserve Notes.

This article was originally printed in Numismatic News.

>> Subscribe today!

The paper money you carry around in your wallet these days has a green Treasury seal on them, which is one of the distinctive characteristics of Federal Reserve Notes.

They say “Federal Reserve Note” right at the top center portion of the face, or front side, of each note.

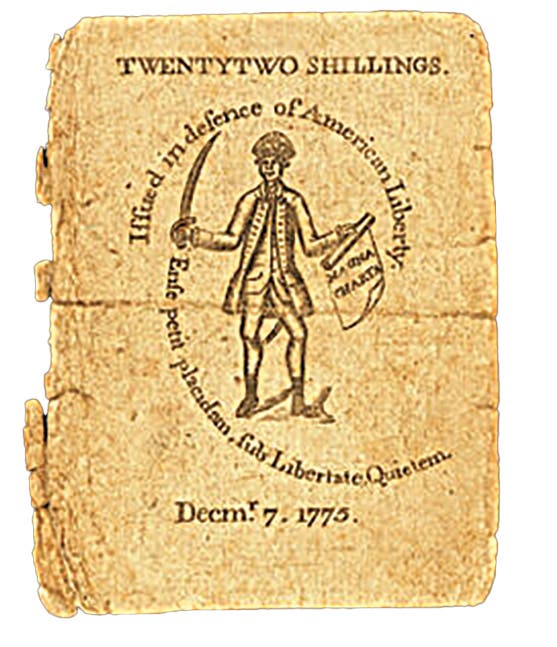

The oldest ancestor of your current Federal Reserve Note was issued in 1914 just after the Federal Reserve was created in 1913. It was one of several kinds of paper money in current use at the time in the United States.

Also issued by the United States were Gold Certificates, Silver Certificates and United States Notes. National Bank Notes were issued by the nation’s local national banks, which had to be federally chartered. These notes were printed by the Bureau of Engraving and Printing and were backed by United States bonds that the local national banks had purchased from the U.S. Treasury. They were considered a national currency every bit as good as the other kinds and these National Bank Notes had the words “National Currency” printed right at the top center portion of the face of each note.

Into this already complicated system of U.S. paper money, the financial crisis caused by the outbreak of World War I in Europe in 1914 pushed the United States to issue yet another kind of paper money to meet demands for cash when everyone was hoarding gold and making it difficult to issue Gold Certificates and to strike adequate supplies of gold coins.

This kind of paper money was called a Federal Reserve Bank Note. It was a hybrid kind of note. Where Federal Reserve Notes were the obligation of the system as a whole, the Federal Reserve Bank Notes were obligations solely of the issuing bank, which was one of the 12 district banks. There are other differences as you will see.

The government printed these notes on the National Bank Note template with “National Currency” printed at the top center of the face side.

These notes are scarce They were issued as a sort of emergency money and the Treasury rapidly retired them when normal conditions returned after the war.

Paper money collectors have known this. There number started increasing rapidly in the mid 1990s and these newcomers helped bid up the prices of Federal Reserve Bank Notes as well as other forms of U.S. paper money.

With rising prices and rising interest levels, it seems safe to suggest that the Federal Reserve Bank Note seems to finally be finding a dedicated band of collectors and as so often happens when one group gets interested and prices start climbing others follow.

As is usually the case, the Federal Reserve Bank Note did not suddenly become scarce and interesting. Rather, it is that many have just suddenly discovered that large and small-size Federal Reserve Bank Notes are both scarce and interesting. For many years the Federal Reserve Bank Note was in many minds confused both with National Bank Notes and Federal Reserve Notes as there are certainly some connections with those other more popular types. The historically important role of the Federal Reserve Bank Note seemed to be basically lost to common memory as was the fact that Federal Reserve Bank Notes as a group are tough and in the case of star replacement notes they can be among the most difficult notes of their era.

With the major powers of Europe engaged in a world war, gold payments were suspended by all, which the exception of Great Britain, which suspended internal gold payments but maintained the gold standard externally.

Pressure in the United States led to the end of striking $2.50 gold pieces with the 1915 issue and 1916 was the last year of issue for the $5, $10 and $20 coins.

The $10 and $20 gold coins came back into production in 1920 and the $2.50 returned in 1925 and the $5 in 1929.

However, to help keep the economy going, Federal Reserve Bank Notes were created with the Series of 1915. What was the backing? Well, at the top of the note under “National Currency” it says “Secured by United States Bonds Deposited with the Treasurer of the United States of America.”

As the war dragged on, the United States was dragged in in 1917, making it the financier of the conflict. One of its obligations turned out to be sending some silver to India to stabilize the currency in that British colony now our ally.

The Pittman Act melted down 270 million silver dollars. This removed from the Treasury the backing for Silver Certificates. They had to be withdrawn from circulation.

They were replaced by Series 1918 Federal Reserve Bank Notes.

Financing a war, then as now, was expensive and it required the “clever” use of paper.

Some $762 million worth of these were issued, but after the war all but less than $2 million were retired.

Possible confusion with Federal Reserve Notes was natural. These notes had only just begun being issued when the financial storm hit, but designs were changed enough to give them a distinctive look, though similar.

On the $10 denomination, for example, the portrait of Andrew Jackson appears in the center of the first Federal Reserve Notes while it is pushed to the far left side on the Federal Reserve Bank Notes.

The Federal Reserve was created with 12 branch banks because the politicians in Washington who created it believed that this would both dilute the power of a central bank (the first in the United States since the Bank of the United States’ charter expired in 1836) and it would diffuse the advantages of having a headquarters to 12 cities in the United States – a big plus to the economic boosters of the day.

The first Federal Reserve Bank Notes were Series 1915. They measured 7 inches by 3 inches like most of the large size notes that had been produced in the United States since 1861.

The first denominations were $5-$20, reflecting the effort to take the strain off gold coins. The $5 was also the lowest denomination of Federal Reserve Note.

Added with the Series 1918 were the $1 and $2 denominations, which reflected the need to replace the Silver Certificates, which were mostly the $1 denomination. Series 1918 also included a $50.

The presence of a $1 and $2 would set the Federal Reserve Bank Note apart from the first Federal Res

erve Notes, which would not include the lower denominations for many years (1963 for the $1 and 1976 for the $2).

Participation in the first Federal Reserve Bank Notes was not universal. The Series 1915 saw only banks in Atlanta, Chicago, Kansas City, San Francisco and Dallas participate and not every bank issued every denomination with San Francisco, for example, using only $5 notes.

The obligation was changed for the Series 1918 with an expansion of denominations and participating banks. The new obligation reads, “Secured by United States Bonds or United States Certificates of Indebtedness or United States One-Year Gold Notes Deposited with the Treasurer of the United States of America.”

That said, every bank still did not issue every denomination with only Atlanta and St. Louis, for example, issuing a $20 for the Series 1918.

The back of Federal Reserve Bank Notes are extremely similar to the Federal Reserve Note. About the only difference was the change in the wording of the indenture at the bottom which spelled out the nature of the legal tender. The Federal Reserve Note was payable in gold on demand while the Federal Reserve Bank Note made no such promise.

The $5 of both types featured Lincoln while the $10 saw Andrew Jackson on the face and the $20 had Grover Cleveland. There is only one large-size $50 Federal Reserve Bank Note and that is from St. Louis, but like the $50 Federal Reserve Note, it has a face portrait of Grant.

With no Federal Reserve Notes for the $1 and $2, there was no confusion with those denominations, and they proved to be special ones at least in the eyes of collectors as the $1 Federal Reserve Bank Note is famous for its defiant eagle on the back while the $2 is even better known as the "Battleship Note" with its steaming period battleship.

It was certainly no accident as with the world of the period engaged in war and America being pulled into a European conflict it did not want to be engaged in, the two denominations really became classic cases of the government using notes to send messages of national strength to the public.

The Federal Reserve Bank Note $1 is available as a type note for a current Choice Crisp Uncirculated-63 price of roughly $350. For a popular large-size note, it is a good price but one which is usually rising. At that price it can be tempting to consider a complete 12-district set, although a complete set is large as the notes come with either a Tehee-Burke or Elliott-Burke signature combination as well as a host of potential combinations for the district bank officials making a complete set much larger than just the 12 districts.

As would be likely with a number of potential combinations, the large-size $1 Federal Reserve Bank Notes are not all equally available. A Minneapolis $1 with a Tehee-Burke federal signature combination and Cook-Young district combination is at $6,000 in Ch CU-63 the key. There are a number of other better notes as well from the Minneapolis, Dallas and Atlanta districts and with increased collector interest it would be no surprise if supplies of other districts and combinations currently seen as available would be found to be inadequate for future demand.

While the defiant eagle on the $1 is popular, the steaming battleship on the $2 is even more popular with many and the supplies of the $2 are lower, which translates into much higher prices. Just for a type note it is at $1,350 in Ch CU-63 with a fine at $250. Although not as numerous as on the $1, there are also still a number of possible signature combinations on the $2, making for a larger than expected collection and some notes command premium prices such as the Chicago Tehee-Burke with district signatures of Cramer and McDougal which recently had fewer than 20 examples reported in a census but despite the low number the notes is still priced with only a modest premium at $2,500. Others run up to $8,700.

The pattern in other denominations is similar with a large-size $5 Federal Reserve Bank Note from an available district listing for $1,450 in CH CU-63 from Series 1918 and $1,750 from Series 1915.

As in other denominations there are better notes especially the Series 1918 where a Tehee-Burke and Bullen-Morse from Boston along with a Tehee-Burke and Clerk-Lynch combination from San Francisco with a May 18,1914 date are both high premium notes.

In the case of the $10 Federal Reserve Bank Notes, they might surprise as they tend to be tougher than many might expect. In the $10 there were limited numbers of issues with the Series 1915 issued only by Atlanta, Chicago, Kansas City and Dallas while the Series 1918 saw notes only issued for New York, Atlanta, Chicago and St. Louis.

You have to be satisfied with circulated notes here, as many of these have no survivors in uncirculated. Prices basically start at $1.050 for a fine example of the 1915 Kansas City issue with Teehee-Burke and Cross-Miller signatures. Up they go from there.

Census totals frequently show totals in the range of 25 known examples for a specific bank in all grades combined.

The $20 FRBN is even more difficult as only a small number of districts issued the denomination. The Series 1915 was issued for Chicago, Kansas City, Atlanta and Dallas while the Series 1918 was even more limited being issued only for Atlanta and St. Louis. With only a few districts issuing what was a higher denomination it should come as no surprise that a $20 even in Fine will be roughly $1,700 for the Series 1915 while the Series 1918 is slightly more at $2,000.

A CH CU-63 Series 1915 will be $16,000 if you can find one with the Series 1918 tending to be less at $8,000. In all cases what must be remembered is that there is really no common large-size Federal Reserve Bank Note.

On July 10, 1929, the United States changed the size of its paper money to the present size, which is called small-size paper money. In October came the great stock market crash, which unleashed the worst financial crisis the United States ever experienced.

It was time once again to call on the emergency paper money created in World War I. It was time for the Federal Reserve Bank Note. Its use was authorized by Congress March 9, 1933, during the bank holiday when the government needed a large sum of paper money fast to keep the banking system from permanent collapse.

Once again “National Currency” appeared at the top of the note as the National Bank Note template was used. The name of the issuing Federal Reserve Bank appeared when the national bank names usually did.

The indenture at the top of the note reads, “Secured by United States Bonds Deposited with the Treasurer of the United States of America or by Like Deposit of Other Securities.”

The words “Like Deposit of Other Securities” were a hasty addition to what had been the usual language on National Bank Notes. Nothing underlined the emergency nature of the notes better than this and it meant the Federal Reserve Bank issuing the note could back it with commercial paper – privately issued financial obligations.

The small-size Federal Reserve Bank Note was printed quite literally on National Bank Note stock. The “President” was blacked out and overprinted with the Federal Reserve District “Governor.”

In most cases the bank cashier’s signature was used meaning no change was required although for New York it was blacked out to read “Deputy Governor” while Chicago had the “Asst Deputy Governor” and St. Louis used "Controller.”

With these small differences, in general the appearance of the small-size Federal Reserve Bank Note could very easily strike some as being identical to a National Bank Note right down to the brown seal on it.

On March 9, 1933, the Emergency Banking Act was passed and

its goal was to create an infusion of money into the economy without requiring gold backing as there had been a dramatic decrease of gold reserves from the Treasury vaults. People were panicked and trying to turn all the paper money they could into gold after the wave of bank failures began in earnest in 1931.

For some reason, the gold $10 coin was in particular demand and the 1932 gold coin mintage of 4.463 million was more than four times the next highest total of the Saint-Gaudens Indian Head series and was the highest total ever produced in the entire history of the gold $10 denomination.

Usually the $20 served for large gold transactions, but the government’s 1928 mintage of 8.816 sufficed as virtually all of the 1929-1933 mintages were never released to the public.

For the federal government, finding additional currency without gold backing was the aim and the Federal Reserve Bank Notes with relaxed collateral requirements met the requirement. The new notes were pushed ahead with record speed and as opposed to the normal 18 months for new notes the first small-size Federal Reserve Bank Notes were on their way in a matter of days.

Most of the notes were delivered before the end of March 1933. All notes that were to be used were delivered by Dec. 21. The bank panic was quelled.

As it turned out, only a small portion of the small-size Federal Reserve Bank Notes printed were actually released. The notes in denominations of $5-$100 saw primarily lower denominations released while only 14 percent of the printed $50s and 21 percent of the printed $100 notes were actually released. The unissued notes were simply stored. Those unissued notes were pulled out of the vaults in the 1940s and released, although the public seemed to view them as suspect causing them to be quickly retired.

As they circulated only briefly and at difficult economic times, the small-size Federal Reserve Bank Note is not a note that saw heavy saving in any grade. If you are content with a note from an available district as an example of the type, getting one is not a significant problem.

A $5 in XF is possible for as little as $50 while a Ch CU-63 would be around $110. In the case of a $10, an available district type note in XF would be $50 while a CH CU-63 would be $150. The $20 is identically priced with an XF at $50 while a CH CU-63 would be $150.

In the case of the $50 and $100, the denomination worked against much saving and that explains why a $50 would be at least $115 in XF and $300 in CH CU-63 while the $100 would start at $150 in XF with a CH CU-63 at $285.

These prices can give the wrong impression as realistically there are a number of tough districts especially in the case of upper denominations. It is also sometimes very difficult if not impossible to find certain notes in crisp uncirculated such as the $5 from San Francisco and St. Louis as well as the $10 from Dallas and San Francisco, the $20 from Dallas and San Francisco along with the $50 and $100 from Dallas.

The $5 from San Francisco is famous for being difficult in CU although the Grinnell collection was supposed to have an example, but that note has not been seen since 1946. That is typical of the situation with some denominations from some districts as even if one or two are known to exist in CU they are probably not for sale and in some cases have not been offered for years.

As tough as the regular small-size Federal Reserve Bank Notes are, the star replacement notes are even more difficult. The stars had printings in a range from 4,000 to 84,000 notes, with the average being about 24,000, which makes any star tough. In fact, even with the low printings, it is the belief of some that in many cases the entire star note printing was not released at all.

We know at present that 46 different stars are known to exist with questions still surrounding the St. Louis and San Francisco $5 as well as the Dallas $50. In other cases the total is so low as to make the note basically impossible to collect as is seen in the Dallas $20 and $100 which are both believed to be unique.

The Chicago $50 is possibly unique and there tend to be one or two districts from every denomination where the number currently known to exist is five or fewer. In fact, roughly one-half of the 46 possible notes have a surviving population currently put at 10 or less, making the opportunity to complete a set a long shot at best even if you have unlimited funds.

A complete collection of star notes might be out of the question, but it is possible to acquire type notes. A $5 would start at $500 in XF with a CH CU-63 listed at $2,000 while a $10 would be $700 in XF with a CH CU at $2,600. The $20 shows an available XF at $500 with a CH CU-63 at $1,750.

The upper denominations are very tough with even an available XF $50 star likely to be $900 or more while a $100 would be $2,000 in the same grade. The $50 and $100 can sometimes be found in CH CU-63 thanks to a couple short runs from Kansas City. While the $50 might be $2,500, any other district will be substantially higher if they can be found at all in the grade. The $100 star is cheaper in the upper at $1,150, but not cheap.

The haunting fact is that large and small-size Federal Reserve Bank Notes have really just begun to be chased by collectors. Compared to coin rarities, there is good value here, especially if more and people decide to collect paper money.

As more collectors discover that the Federal Reserve Bank Note is tough and with an interesting history, demand is likely to increase. With such limited supplies of so many notes in a complete set, that is likely to produce even higher price and greater competition for some of the best Federal Reserve Bank Notes when they hit the market. Under the circumstances, even if you simply want nice type notes the time to get them is certainly now before the competition gets any more intense.

More Coin Collecting Resources:

• Subscribe to our Coin Price Guide, buy Coin Books & Coin Folders and join the NumisMaster VIP Program