European Union Rejects Coin Design

Monnaie de Paris, the mint of France, minted coins with a new design. The design had not yet been approved by the European Commission. The EC later rejected the design.

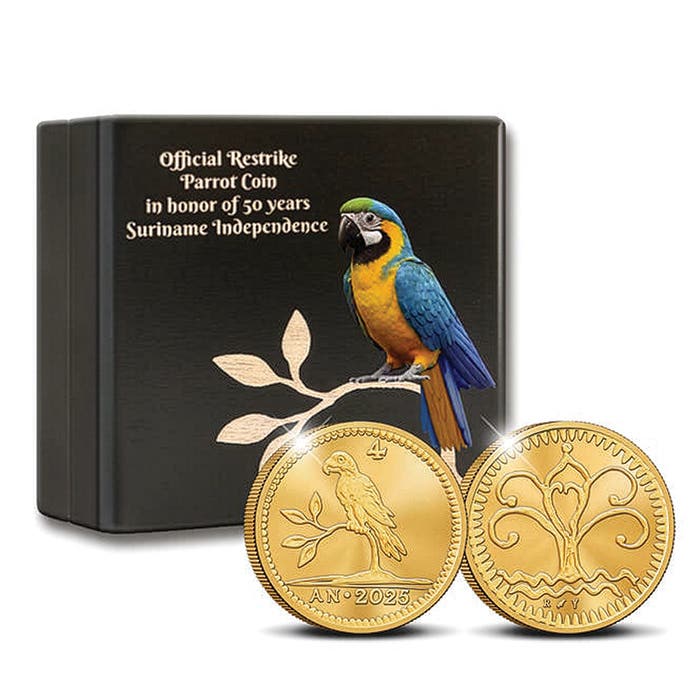

Images on coins can be controversial. There have been several instances when a map of a country or region redefined the outline of one or more other countries, sometimes by accident and other times not. There have been coins showing the Olympic rings, that country not having participated in the Olympics. There have been coins issued in the name of a country, but the government of that country had not approved the issue. There is an ancient Roman coin on which a victory was celebrated, but in fact, the Romans lost that war, and the emperor was captured by the enemy.

It now appears France has joined this dubious group but with a new twist. Another country was able to protest, but not able to stop the issue of any of the examples cited above. Monnaie de Paris, the mint of France, minted coins with a new design. The design had not yet been approved by the European Commission. The EC later rejected the design. Now, the mint is taxed with destroying and then minting about 27 million coins to replace the rejected issue.

It may appear to be petty, but the EC rejected the proposed redesign for the national side of circulating French euro coins because they felt that the stars representing the European Union were too difficult to see.

France is a member of the European Union’s currency union. As such, France issues coins and bank notes in euro denominations but must comply with the currency design approval stipulation by the EC as a condition if they are to participate in the currency union. The EU side of each coin must show a previously approved generic design representing the EU. The design appearing on the other side, known as the national side, can depict whatever the issuing government desires—once approved by outsiders. EU law allows eurozone participants to redesign their national side every 15 years, but that design must be approved by the EC. Other participating eurozone members have one week in which to voice any objections to proposed new designs.

Monnaie de Paris Chief Executive Officer Marc Schwartz authorized new designs for France’s 10-, 20-, and 50-cent euro coins during November 2023. The plan involved unveiling the new designs to French Economy Minister Bruno Le Maire during Le Maire’s upcoming visit to the mint on December 7. Sources indicate France did informally contact the EC regarding the proposed design change in November. Schwartz didn’t wait for approval but began producing the new coins. Soon after, the EC sent France an informal warning that the proposed design did not comply with EU rules.

On Dec. 1, the EC formally rejected the new coin designs. The unveiling for the economy minister scheduled for December 7 was canceled. On December 12 the French treasury submitted a corrected design to the EC, which on December 21 was formally approved.

In the wake of all this, Monnaie de Paris was faced with melting the rejected coins, striking coins with the appropriately approved design, and a bill for all this estimated to be between $768,000 and $1.6 million. The scramble was soon on about who was to blame.

Le Maire deflected to Schwartz for the situation, stating that Schwartz indicated the postponement had been beyond his control. Le Maire nebulously blamed the situation on the “French State.”

The French Economy Ministry followed this up, stating Monnaie de Paris requested approval of the design “in accordance with existing procedures.”

According to a Monnaie de Paris statement, “Given the incompressible production deadlines, the Paris Mint had initiated the production of the new coins to ensure the distribution of the new standard coins at the start of 2024, in accordance with what was initially announced.”

A panel led by the Minister for Economic Affairs and Finance chose three designs for France’s initial euro coins. More than 1,200 designs were submitted. A portrait of Marianne, a symbol of the First French Republic, was chosen for the 1-, 2-, and 5-cent euro coins. A stylized tree within a hexagon appears on the national side of the 1- and 2-euro coins.

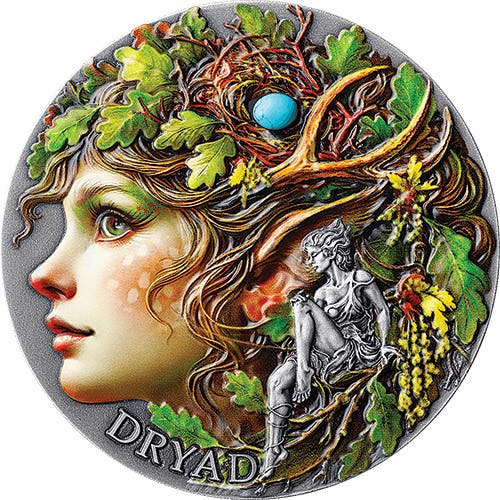

The national side of the French 10-, 20-, and 50-cent euro coins each feature “the sower,” a design theme initially created by Oscar Roty to represent “France, which stays true to itself, while integrating into Europe.” The Roty design was carried over from the former French franc. The central design element is surrounded by 12 stars, these stars representing the 12 initial EU member nations.

The coins to be destroyed and replaced represent less than two percent of the mint’s annual output. The bigger question for coin collectors is how many of these rejected design coins will fall out of the melting pot and go out the back door.