English gold penny didn’t last long

After the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the latter part of the fifth century, the use of coins in daily life underwent a dramatic transformation. The ordinary people…

After the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the latter part of the fifth century, the use of coins in daily life underwent a dramatic transformation. The ordinary people resorted to barter and only the wealthiest had use for coinage of any kind. Trade slowly revived, however, and in due course there were commercial affairs between the new nations. For such purposes small gold coins were struck but very little silver.

In Anglo-Saxon England gold was first minted late in the sixth century and during the first half of the seventh century a fair amount of such coinage was minted. The common person never saw any of it as each piece of gold represented many months of work. Wealthy merchants and nobles used this money for imports and hoarding. There were also donations to the church, part of which found its way to the papacy in Rome.

Towards the end of the seventh century gold supplies began to fail and the numerous French mints began striking silver instead of gold. This meant that internal trade was reviving and cities were once more beginning to bustle with tradesmen selling a variety of products. There was thus a small return to a money economy in urban centers though most transactions in the rural areas were still by barter.

By late in the eighth century, under King Offa of Mercia (the principal English kingdom), minting of silver pennies had become widespread, though of course, money did not reach all classes of the public. But coinage continued to increase until by 1000 C.E. in Anglo-Saxon England it was a rare person that did not handle a silver penny on at least an occasional basis.

William the Conqueror invaded England in 1066 and seized the throne but did little to change the English monetary system. The silver penny continued to be struck in great numbers in many cities but gold virtually never. On rare occasion before 1066 the English authorities had struck some gold coins (from penny dies) but these pieces were meant primarily as religious offerings and presents, not currency.

In due course, as trade became increasingly important in Western Europe, merchants felt the need for larger silver coins, so that making payments was not so time-consuming. Counting out a large number of silver pennies was not a pleasant way to spend one’s time.

In 1252 the Republic of Florence in Italy began striking a gold florin for its merchants and the idea spread quickly. A few years later King Louis IX introduced gold coins to France while shortly after that the Kingdom of Naples, also in Italy, joined the list. In the 13th century Italian merchants were the most important in Europe, due to their mercantile abilities, and their ideas bore fruit throughout Western Europe.

By 1256 King Henry III (1216-1272) of England was considering issuing his own gold coin. Son of the famous (or infamous) King John, Henry ordered such a coinage to be made in the summer of 1257. On Aug. 16 of that year he issued a proclamation commanding the public to accept his new gold coins at 20 pence (1 shilling 8 pence) in all transactions.

The new gold coins weighed about 45 grains each (slightly less than 3 grams) compared to only a little over 20 grains for the average silver penny. In addition the gold coin had a larger diameter. Oddly enough these coins had no intentional alloy and were struck from nearly pure gold. Even the pennies were made from sterling silver, which contained a small amount of copper for hardness.

For comparison it can be noted, for example, that the United States cent piece struck before 1982 weighs 3.11 grams, or 48 grains. Gold is of course heavier than brass so the gold penny of 1257 is slightly smaller than a U.S. cent.

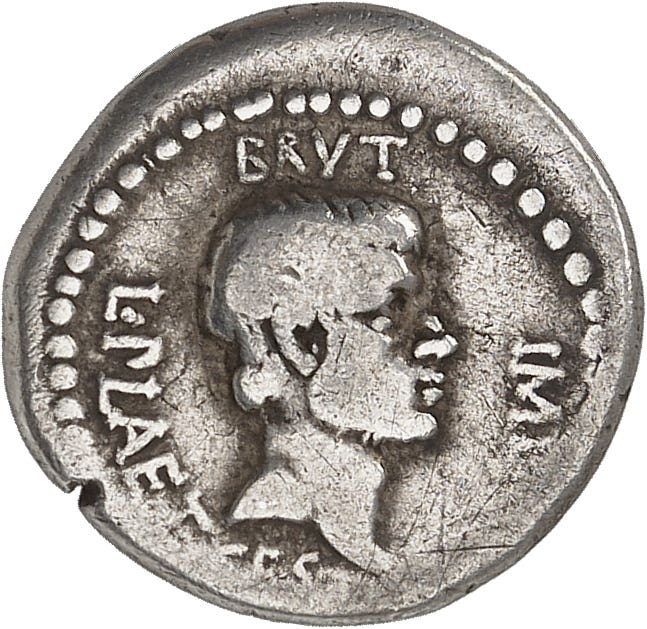

The gold coin is spectacular compared to the average poorly struck silver penny. On the obverse the King is shown seated on an ornate throne surrounded by the legend HENRIC REX III or “King Henry the Third.”

The reverse has the standard (for the time) long cross reaching to the edges of the coin. There is a rose surrounded by three pellets in each angle of the cross. The legend reads WILLEM ON LVND or ‘William [coiner] at London.’(Spelling variants for the name London include LVNDE and LVNDEN.) William’s full name was William de Gloucestre and he was goldsmith to Henry III as well as an important moneyer at London.

Henry picked a bad time to introduce his new currency. The so-called Mad Parliament met the following year and tried to depose him over a variety of matters as inflation was rampant throughout the country due to crop failures. A measure of wheat which cost 7 shillings in 1255 now cost 24 shillings. Hunger stalked some parts of the land and the economy was in serious trouble.

Within a matter of weeks London merchants rebelled against the new gold currency, telling the King that it was undervalued at 20 pence and ought to be worth more. The Lord Mayor of London even presented a formal petition to the King on Nov. 4 with these arguments spelled out in detail.

Faced with other troubles, Henry III did not need a dispute with merchants over the value of a gold coin and issued an edict stating that the coin would pass for whatever was agreed to by the consenting parties. Those wishing to redeem their coins for silver pennies at the Treasury might do so but the government would deduct one-half penny (2.5 percent) for the recoining costs.

Despite these setbacks it is believed that the London Mint continued to strike the gold pennies for another year or two. It is not clear from the surviving records just when the minting stopped, but as William de Gloucestre was murdered at Southampton in 1262 the coins cannot be of a later date.

In 1265 the value of each gold coin was raised by proclamation to 24 pence (2 shillings) but this rate had probably been in effect for some time in the marketplace. There are a few minor mentions of this coin in the royal records as late as 1270 but after that there is only silence.

It seems certain, due to the number of dies known, that a relatively large number of these coins was originally minted but most were later melted or exported to the continent, where they were also eventually used as bullion by the various national mints. Many of them seem to have gone to Italy in payment for luxury goods.

Only a handful of these coins are known today, most of which are permanently impounded in museums. Priced catalogs do not bother giving a collector value for the gold penny because of its extreme rarity.

Henry III made no further efforts towards a national gold coinage but in 1343 under Edward III (1327-1377) a fresh start was made by striking gold florins and its fractions. Unfortunately the new issue faced many of the same problems that arose in the 1250s and the coinage of 1343-1344 had to be called in. There were other false starts but within a few years the government was able to create a circulating gold coinage.

The illustration with this article is from a drawing made in the late 1740s, at the direction of Martin Folkes, as it shows the details of the coin much better than any photograph could do.

This article was originally printed in World Coin News. >> Subscribe today.

More Collecting Resources

• The Standard Catalog of World Coins, 1601-1700 is your guide to images, prices and information on coins from so long ago.

• When it comes to specialized world paper money issues, nothing can top the Standard Catalog of World Paper Money, Specialized Issues .